The only long-term side effect you see from vaccination is life.

Christian Kinlin

On Thursday, Nov. 18 via Zoom, Seattle Central College’s library hosted another Conversations on Social Issues (COSI) featuring Christian Kinlin, a STEM-B lab technician at the college. According to promotional materials, the conversation, provocatively titled “Do Your Own Research for Vaccines,” set out to address “conflicting information on vaccines in the media” and to discuss “the clinical approval process, and pharmacology of vaccines.”

Kinlin’s expertise lies in government regulation of vaccines as opposed to human psychology, but the COSI audience specifically wanted to discuss why so many contemporary Americans have shied away from COVID-19 vaccination. One audience member recalled that when the government began vaccinating children against polio, the public didn’t react negatively.

“There were anti-vaccine folks when the polio vaccine came out,” Kinlin explained; however, he went on, “there was less deliberate misinformation the way that we have now.” As an example, Kinlin cited the flawed research “that linked vaccines to autism.”

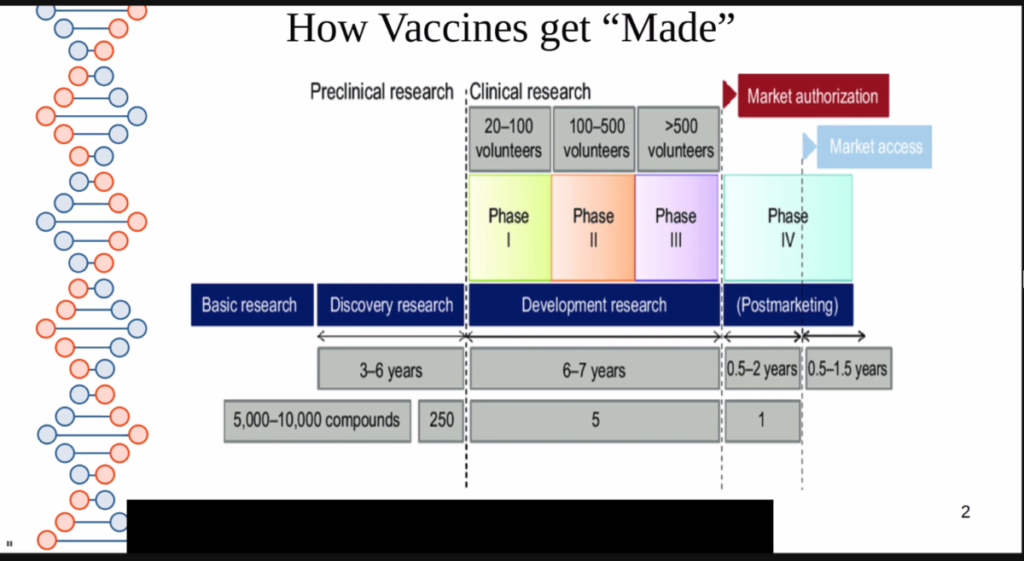

Moving beyond misinformation, Kinlin shared a slide illustrating the process of vaccine development and FDA approval. The process begins with preclinical research, which includes a discovery phase and may take 3-6 years. This phase of development may include animal subjects. Human volunteers get drafted during clinical research, a multi-phased affair that may take another 6-7 years. Next comes market authorization and market access, stages that may take an additional 4 years.

If you follow the math, you see that it can take 16-17 years to develop and market an effective vaccine. “The reason it normally takes so long,” Kinlin explained, “is that [researchers] have to find patients suffering from the disease.” For example, in the case of human papillomavirus (HPV), it took a long time to develop a vaccine because the disease itself progresses so slowly and many infected individuals don’t know they have it.

By contrast, COVID-19 vaccines became available to the public in less than a year. Because the virus spread so quickly in the early stages and the mortality rate initially hovered around 5%, Kinlin said, “[Researchers] easily found volunteers.” Ironically, the early success of the virus contributed to the speedy development of the vaccines that could eradicate it.

And yet, according to the CDC, 41% of Americans remain unvaccinated. Kinlin went on to say the virus mutates in unvaccinated people. If too many people remain unvaccinated, the coronavirus can morph into new vaccine-resistant strains, rendering the 59% of fully-vaccinated Americans vulnerable to new and possibly more deadly infections. Complicating matters, COVID-19 cases have risen by 20% in the past two weeks. As holiday travel increases, health experts fear that numbers will rise, putting unvaccinated citizens at risk of hospitalization and death.

“Our best bet at this point is to keep the infection rate low,” Kinlin said, meaning we need to see more people getting vaccinated.

Kinlin went on to speak on the benefits of vaccines in general. Excepting small, isolated pockets, he noted, we’ve wiped out smallpox and polio with vaccines. We’ve developed vaccines for chickenpox, cholera, influenza, hepatitis, measles, mumps, rabies, rubella, typhoid, and yellow fever. Given the truth that vaccines can eradicate so many health threats, it’s puzzling that so many Americans choose not to get vaccinated.

Leaving the event with a desire to understand more about vaccine-reluctance, the Collegian emailed Seattle Central psychology professor, Shaan Shahabuddin. He said that cognitive biases like optimism bias, the belief that bad things won’t happen to you, and confirmation bias, the embrace of “information that supports” what you already believe, inform how people make decisions. People who already oppose vaccines, for example, “may only look at evidence that supports their belief that vaccines are bad.”

Kinlin’s COSI clearly presented the evidence for why vaccines aren’t bad. They may not be “a panacea,” he noted, but they do “reduce mortality.” Plus, coupled with masking and social distancing, they represent a way out of the pandemic.

For more information on the efficacy and side effects of the COVID-19 vaccines, you can watch Thursday’s COSI at Seattle Central College’s library website. Check it out. It’s worth a shot.

For updates on future COSI’s, visit the Seattle Central College Library website. Sessions are held most Thursdays via Zoom for free, with recordings and presenter slides available within a few days of each live event.

Be First to Comment