Inland Empire (2006) at The Beacon Cinema

I could lie to myself, but I won’t. Inland Empire (2006), presented at the Beacon Cinema, was monotonously schizophrenic. There will be a point in the stuffy dark, after and amidst all the nonsense where you’re trying to remember the plot, that you realize you will never get these three hours back.

Inland Empire is David Lynch’s experimental forray into digital filmmaking, his only feature film after the turn of the century, and you have to wonder why he hasn’t made another film since this. There was no finished screenplay; it was developed and shot scene-by-scene over three years with a Sony handheld camcorder. Dream logic is the rule here. It’s the type of movie that sounds pretty good on paper, but three hours of Lynch off his leash is… untenable.

Let me try to siphon the plot, just for you. The film stars Laura Dern as an aged actress trying to recapture the light. She’s got this scary husband – some big swinging dick in Hollywood – and glory be when she is cast in what turns out to be a remake of an unfinished film in which the actors were murdered. Slowly, she begins to lose her mind, unable to discern between the film and reality, or if there ever was a difference to begin with.

I’m getting ahead of myself.

The Beacon Cinema, 4405 Rainier Ave S. A quaint joint, and on a good day, maybe even charming. It’s a little fourty-seat, single screen theater, blink-and-you’ll-miss-it type spot. What happened that night wasn’t her fault, but she’s no less an accessory to the fact.

“We are like the spider. We weave our life and then move along in it. We are like the dreamer who dreams and then lives in the dream. This is true for the entire universe.” This is a quote from the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, which Lynch will read when presenting screenings of film. It’s considered one of the few keys Lynch has given the film’s meaning, which he has otherwise declined to comment on.

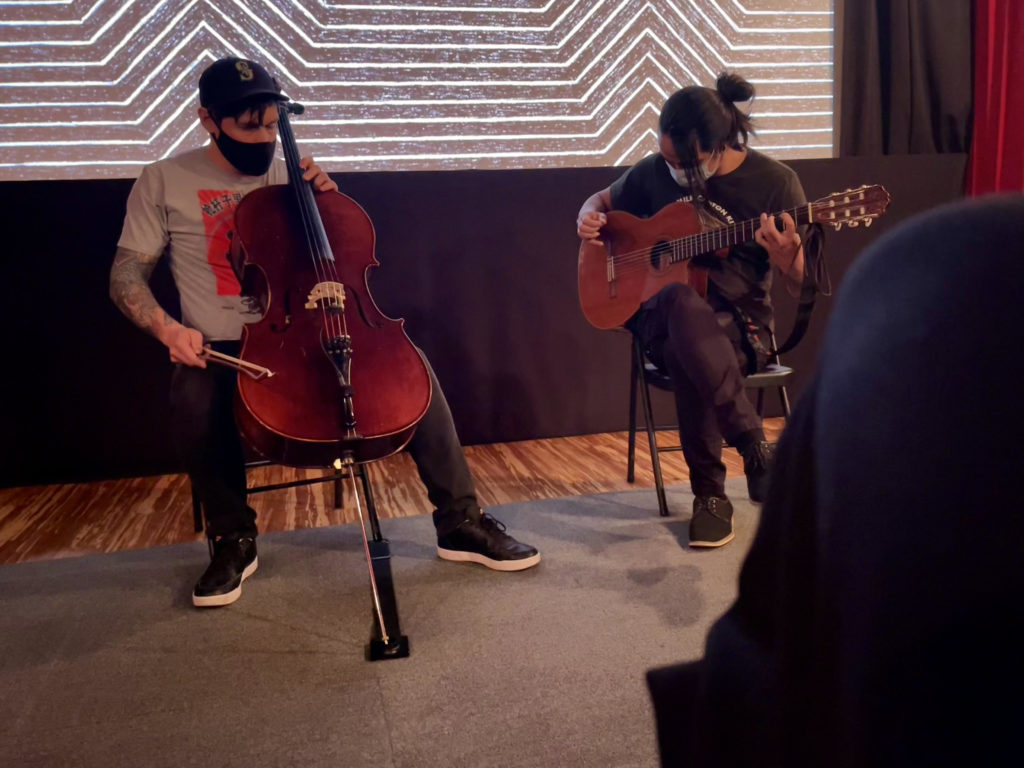

We should’ve known… We should’ve put two and two together. When my brother and I walked in, there was a man tuning his guitar. Taking our seats in the very front row (of five), there was a bass on the floor before the screen. A pause worthy of note – I was growing nauseous and the oily popcorn air was still tempting; all I had to eat that day was iced coffee. Exit the bathroom, and the concession stand is unattended, “be back soon”, scrawled in fat sharpie. I hover, only for a second, then return to take my seat.

Scouts honor. I walk in and the house lights are up. Two men are mid-orchestral number. I’m so taken aback that I stop in the doorway, make dead eye contact with my brother, and we’re both holding back laughter. Apparently they read off that little script above, and just cracked into it. Everyone is stone-faced as if they entirely anticipated it, and that this was perfectly normal. Trust, also, these two men were quite talented, like the whole gimmick was good, but so utterly jarring.

The lights go out, the film begins, I’m up the creek without a kernel, and my brother and I are still reeling.

Earlier that day, a guy accused me of never having experienced ego death, and I can confidently say, now I have. This film is about submitting to an experience, in the least romantic way. Laura Dern submits to her dream, as if she ever had a choice. You submit to three hours of masturbatory nonsense; you submit to the fact that the girl next to you won’t stop picking her scalp and checking her nails. You can’t breathe, it’s too hot. You are here right now.

The beginning is strong, and the shaky handheld footage actually supplements it. You feel like a voyeur, but as the film runs on, it begins to feel more like someone has been holding their Facebook vacation montage in your face for way too long. You want to tap the screen to see how long is left, but you have no service. Open Q to Beacon and affiliates: Are there signal blockers in your theater?

Lynch’s strong suit has never been character nor plot, but he’s lethal when it comes to the creation of energy and aesthetic. And when he really leans into that, those are the brief glimpses of pleasure during this movie. Simultaneously, it feels like he’s laughing at the audience, stringing nonsense together to listen to people vaguely gesture at meaning that just isn’t there. A film doesn’t even have to mean anything, but this is just an exhausting exercise. I’ll acquiesce, maybe I oughta give her a second go, but there’s no fiber of my being that desires to. This might be one of the worst films I’ve ever seen. I don’t even know if I can give him points for caring.

This is Lynch uncut, unfiltered. The epitome of his dream logic, him exercising total control to a fault. There’s nothing to reign him in: entire portions of this film could and should have been cut. A three hour film, in theory, is going to necessitate its length, and this film feels like it is working tirelessly to achieve the length. The film felt without aim, as if it were about to end every five minutes. The entire theater slowly grew restless. You could’ve heard a pin drop during that unnamed orchestra performance, but an hour and some change into the show and there begins an unending chorus of shifting, whispering, and people rising for concessions. This dude in Chelsea Docs and a red, wool suit is the only trooper still invested when the credits roll. I’m happy for him.

Victoria Winter is trying to prove that nothing human is alien to us. On paper, she is a second year student at Seattle Central College, potentially majoring in anthropology and philosophy. In reality, she is fascinated by using the mediums of photojournalism and writing to explore subcultures - the fringes, the limelight, and everything in between. She is in love with humans. Her only firm beliefs are that everything should be explored and most things are easier at night.