Op-Ed: Gender-affirming care doesn’t need to invoke intense joy: only stability

Every morning I’d pick up my discarded binder and try it on multiple times.

I had been poking at the line between masc and femme for over a year, hoping that whatever presentation would make me euphoric would jump out at me. I fumbled with bold eyeliner, got too many awful haircuts, played with clothing color, and tested my vocal range.

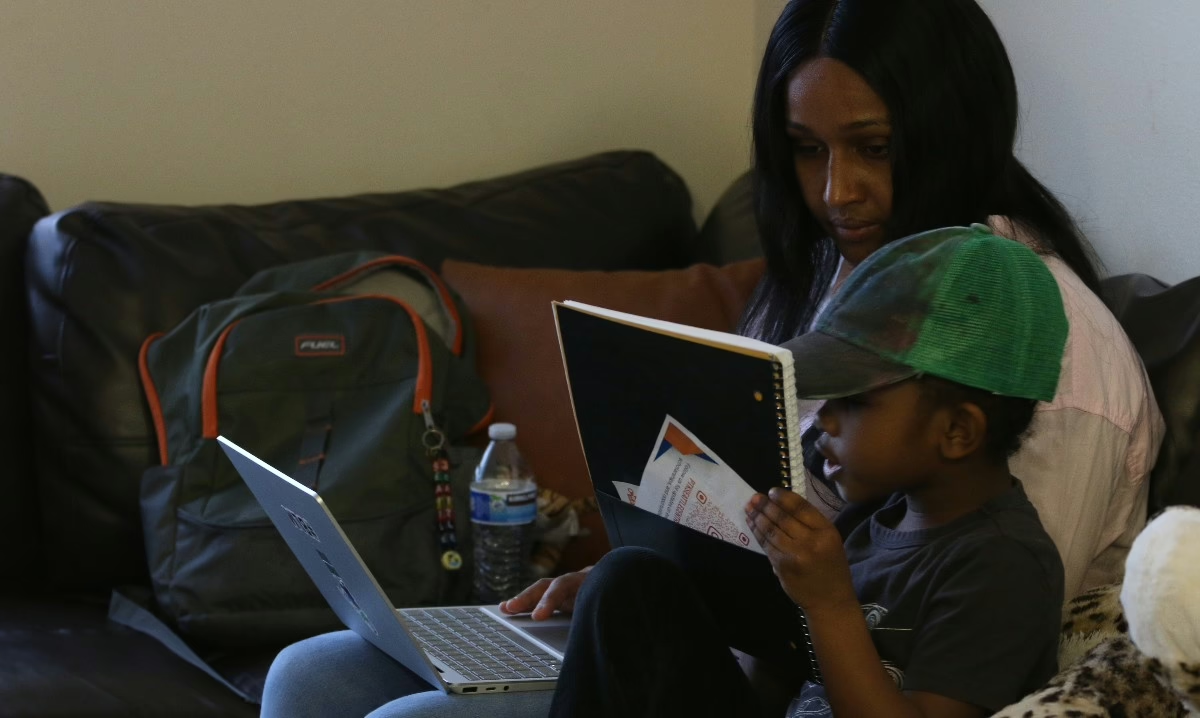

A chest binder had only recently joined the mix, mostly because I was worried I’d like it so much I’d need top surgery. The surgery was expensive, I didn’t have the health insurance to cover it, and a month-long recovery sounded daunting. Eventually, a roommate made me an Excel sheet we lovingly called “boobn’t,” and it tracked the days I woke up feeling like I loved my chest, and the days I didn’t love it as much. I remember being incredibly surprised to see myself constantly checking the “I don’t want my chest” box.

Even with the fancy graph my Excel sheet made and the countless data points of proof I had, I was doubtful that I really wanted it. Every day I scrolled social media feeds, folks crying in joy after their surgeries, people talking about how their surgery saved their life, and rightful worries about stringent access to care. I never felt the same emotional intensity I was seeing in portrayals of trans people, and for a while, I questioned whether or not I was really trans.

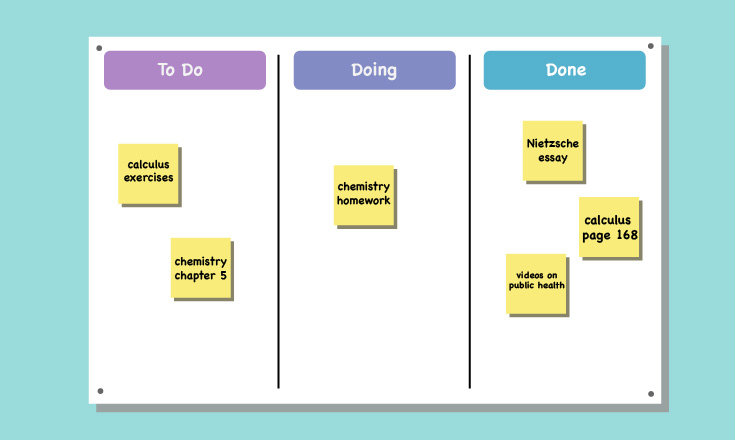

But I pursued top surgery anyway. Nothing had particularly changed emotionally, but I didn’t feel scared about my surgery, or like I’d regret it. I found a job that would give me health insurance after a certain amount of hours, scoured through insurance documents to figure out whether or not the surgery would be covered, and made phone calls in a bleak attempt to figure out what the first steps were.

It was clear early on in the process that I could never show or talk about my hesitations because the entire process revolved around proving how trans I was. The WPATH letter needed for top surgery includes a gender dysphoria diagnosis, and if I voiced concerns with the wrong therapist, the process could become lengthier. When I met with a new primary care provider — having one was a requirement — I was afraid to talk about my hesitations. It felt like top surgery could be taken away entirely, dismissed as my period or stress, like medical concerns in female bodies often are.

Hesitation, at that point, was a luxury I couldn’t afford. Sometime during the process, I genuinely forgot about my doubts because I had been pushing so hard to prove that I was really trans, there was no space for any negative emotions surrounding the surgery. My WPATH letter was sent back to me more than once, each time asking for more detail about what my dysphoria was like. I talked about cutting my hair, putting on the binder over and over again, and the Excel sheet, but none of those were enough. The next letter dug into my childhood, talking about how I never liked sports because of how my chest moved, how I cried about wearing a dress before a dance and couldn’t express what was wrong with my limited queer vocabulary, and how the worst part of being on birth control was my growing chest. In the next letter, they wanted information on my OCD and PTSD, which I had received a diagnosis to get medication for. My therapist raised an eyebrow and asked if it was really necessary to include that information, and I wondered the same, but with no other options we added it to the letter anyway

The entire process was painful and incredibly intrusive, forcibly reaching into the depths of trauma to convince cisgender doctors that a feeling they never experienced was real. Getting an acceptable letter for surgery took over six months, and scheduling between myself and the hospital took another six.

I only remembered my hesitations a week before the surgery, and was immediately plagued by a fear that I had gone through all that trouble only to decide I didn’t want it. Discourse about people who had regretted their surgery was becoming popular on social media, which only made me feel more uneasy. It took the surgery being canceled for me to realize my hesitations were based on the process of surgery, not the outcome.

Surgery itself — getting the letters, going to the doctor’s office, going under, dealing with recovery — is hard, and to be allowed to get it I had to seem ecstatic about it. When I changed my name and pronouns, I had all the time in the world to go through the grief and doubt that comes with change. I worked through my emotions, made pro/con lists, and revealed the change to my community when I felt ready. I am happier now than before I changed those presentations.

When the surgery was canceled I lost something that felt comfortable and stable. My new name and pronouns had felt the same. There was so much pressure to be 100% sure alongside intense feelings of joy, to convince doctors that I needed the surgery, and to convince myself I was just as trans as the people I saw online. I was never allowed to fully explore why doubts were there in the first place.

I don’t want to dismiss trans joy, I’m happy that the people who posted videos had an avenue to celebrate. The medical system is the piece of the puzzle that worries me. It put so much pressure on me, forcing me to never waiver on my feelings, and went as far as to make me doubt my own identity. Doubt was imposed on me, and has been on others, and as a result, I had developed an inaccurate sense of what being trans looks like. Surgery is not easy, it involves high costs, a need for a support network, and a lengthy uncomfortable recovery period, and I’m disappointed by the system that told me it should be something joyful.

It turned out that I desperately wanted the surgery (mine has since been rescheduled), but I think often about others in the opposite situation to me, who went through with gender-affirming surgery and regretted it. I wonder if a little more space in the medical system to explore their doubts would have helped them, it certainly would have helped me. Limiting emotional exploration, while also forcing trans people to share their deepest emotions with multiple parties, helps nobody.