Pacific Northwest Ballet’s ALL PREMIERE in Review

If you’re going to do one thing this week, you should vote. If you’re going to do two things, you should vote and see Pacific Northwest Ballet’s ALL PREMIERE mixed rep. If you are under the age of 19 or a student, you are in luck: your ticket could be anywhere from $5 to half off if you purchase at the box office on the day of the performance. With a strong selection of pieces featuring a diverse range of dance styles, the night manages to thread together alternative rock music, succulents, pointe shoes and operatic singing in a surprisingly coherent performance. All three of the very different single-act shows fit together cleanly, with each act almost in response to the last despite their different origins and standalone natures. First off, we have a world premiere from PNB soloist dancer, Kyle Davis, titled A Dark and Lonely Space.

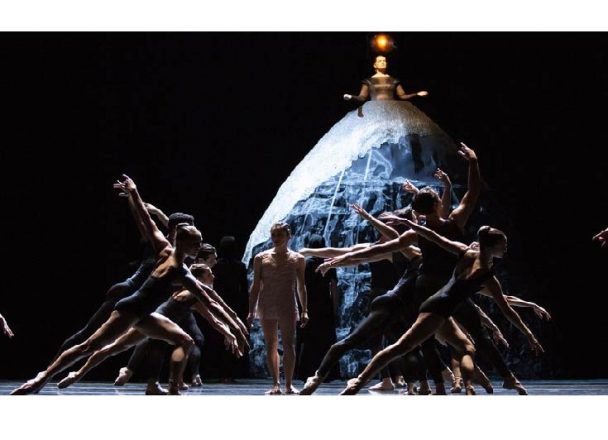

Overall, A Dark and Lonely Space invokes a feeling of cosmic existential awe. The ballet was described by Davis as ‘the anthropomorphization of the birth of a planetary system.”

The music leaves you with the impression of a vast expanse all wrapped up in a gravitational drama of ends and new beginnings in a cycle as old as time. Using the score from the film Jupiter Ascending was an interesting choice, especially due to the lack of success the first project set to that score experienced. The music was performed live from the pit (and the balconies!) by a large orchestra and a sixty piece chorus, as well as a soprano soloist onstage. The chorus that performed is a group from Pacific Lutheran University. The choral rhythmic harmonious almost chant-like aspect lended a feeling of some inner workings of a mystic string-puller to the dancers in masks and the singer in the tall and looming statuesque dress. Giacchino often puts “made up words” into his choral vocals, along with his childrens’ or pets’ names. You could tell that there was a lot of work put into the music and how the dance interacted with it, so it is not surprising that the choreographer, Kyle Davis, said “Music is absolutely the most important thing.” Music was occasionally given literal stage time, where dancers would freeze or sit in reverence to the orchestra and chorus or the onstage soprano.

The ballet has an unusually gender irrelevant protagonist; the first cast is Leta Biasucci, but the alternative cast for the role are Ezra Thompson and James Moore. There is female-female partnering in first cast, but alternative casting means there is also man-woman or man-man partnering. In an art form deeply steeped in tradition, this is still a profound message. Diversity will continue to grow and shape art, even in an art form as specific and often predictable as ballet.

Lights shaped the stage brilliantly, at one point stripping the huge stage down to a narrow strip of illuminated scene. In the dark, the stage could be a million light years across, cold and dark and lonely. Light and scene designer Reed Kakamaya deserves special recognition.

The piece ends suddenly and thrillingly, leaving the audience questioning and shocked.

There was an impressive combination of styles, with a modern-interpretive dancing protagonist, a modern quartet, and an 18-dancer ballet cast (6 corps men, 6 corps women, 3 featured men, 3 featured women). The costumes were equally diverse; some dancers were barefoot, others en pointe; some wore long dresses, others leotards and tights. Costumes were designed by PNB principal dancer Elizabeth Murphy (who performed that night in Silent Ghost).

There were four sets of characters in A Dark and Lonely Space: the Protagonist (and their mysterious partner), the 15 foot soprano, the four hooded women, and the ballet cast. The Protagonist is innocent and exploratory, and over the course of the ballet discovers the limits and possibilities of both their body and emotions. The quartet had an abundance of religious imagery in their ritualistic patterns and long nun-like dresses. The addition of hoods and masks turns the nun into cultists, but they remain benevolent to the Protagonist and hold some connection to the onstage soprano.

The balletic ‘space dust’ ranged from militaristic precision to powerful athleticism to waves of magnetic attraction/repulsion to weightlessness and romance drifting aimlessly through space. They had a ballet aesthetic with the standard uniform of tights and leotards and pointe or technique shoes. But their aesthetic was not classical ballet– more Balanchine or even Forsythe than Petipa, given that there is no tutu in sight and the movements can be off-center and athletic; as opposed to the illusion of ease in ballets like Swan Lake or Nutcracker.

Standout performer roll call: Newly promoted principal dancer Leta Biasucci was convincingly naive and exploratory, displaying strength, grief, loneliness, and love through little more than body language and interpretive dance vocabulary. Noelani Pantastico held a powerful, almost menacing presence over the stage with her stellar (get it?) execution and subtly precise demeanor. She and her partner Seth Orza had remarkable musicality both in their partnership and their solo work. Soprano Christina Siemens, who never leaves the stage (though has some breaks in the darkness) had a remarkable resonance and magic in her performance, representative of the deity or celestial body she symbolized.

The next ballet, Silent Ghost, continues choreographer Alejandro Cerrudo’s signature of a diverse set of music, ranging from indie alt rock to atmospheric ambient sound or a somber piano solo.

Even in the huge theater, the subtlety of the performers and choreography burrowed into my brain, leaving me thinking about it for days.

This piece was about 18 minutes long–much shorter than the 45 minute runtime of A Dark and Lonely Space. Doug Fullington, the Audience Education Manager for PNB, describes Silent Ghost as “intimate and sincere … without chiche or [even] necessarily sentimentality.” This rang very true in my book: it felt as if the audience was peeking into the inner workings of several relationships. Even in the huge theater, the subtlety of the performers and choreography burrowed into my brain, leaving me thinking about it for days. The soundtrack was in large part a blend of mediums that brought me to wordless tears. The second track, a mix of ambient piano and intimate everyday living noises, definitely pulled at the heartstrings. The contemporary dancing could be smooth and fluid, or at times painfully sharp. An incredible addition to PNB’s repertory, this is Cerrudo’s third piece to grace McCaw hall, and if I’m honest I’m a little impatient to see a full evening of Cerrudo in the future.

Standout performer roll call: Principals Noelani Pantastico and Lucien Postlewaite looked as if they were made for contemporary dance, with a sense of both hesitancy between their characters and a quality of familiarity between the dancers. Pantastico had a good night, remaining poignant in her next partnership too– this one another instance of woman-woman partnering. James Moore stood out in the group work, though I can’t explain exactly what set him apart. Dylan Wald, still a member of the corps, is incredibly suited to Cerrudo’s work, shining like a star while remaining deeply grounded. His partnership with the equally radiant principal Elizabeth Murphy brought me to tears, though that too I cannot explain. It’s worth mentioning that Wald made me cry last year too, in the finale of Cerrudo’s Little mortal jump.

Hoo boy. The third act of the evening, Cacti, is probably the funniest piece of dance I have ever seen (sorry Jerome Robbins; I still love The Concert with all my heart). Even with genuinely stunning choreography and visual design, the p iece’s true core is its narrative of a dance critic trying desperately to find meaning in the abstract dancing. The best part of the piece, to me, is the level of accessibility it has. Humor is notoriously difficult to get across in dance. Dance is also notoriously exclusive, with the finer points often only understandable to people educated in the subject. In Cacti, Alexander Ekman manages to not only be hysterically funny, but also poke fun at critics and the pretentious high society that comes with them. Anybody can come see Cacti, and be entertained by the synchronicity of the dancers, the absurdism of the movements, the vocals (both pre-recorded and screamed by the dancers) and the satisfying use of music and scenery. The voice-over of what might have been the conversation between the duet near end was incredibly entertaining. The lighting was used both aesthetically and humorously to great effect, at one point descending from the roof of the theater to end dangerously close to the dancers. Like, a-foot-away close. The costumes included caps full of powder, which is released into the air upon slapping the top of the dancers’ heads. And of course, the prickly cacti make appearance. They are revered as idols, they are thrown to the floor, they are incorporated into a sculpture, they are used for dick jokes—everything you’d expect from a night at the ballet, right? But what could it mean? That’s for audience members to decide.

iece’s true core is its narrative of a dance critic trying desperately to find meaning in the abstract dancing. The best part of the piece, to me, is the level of accessibility it has. Humor is notoriously difficult to get across in dance. Dance is also notoriously exclusive, with the finer points often only understandable to people educated in the subject. In Cacti, Alexander Ekman manages to not only be hysterically funny, but also poke fun at critics and the pretentious high society that comes with them. Anybody can come see Cacti, and be entertained by the synchronicity of the dancers, the absurdism of the movements, the vocals (both pre-recorded and screamed by the dancers) and the satisfying use of music and scenery. The voice-over of what might have been the conversation between the duet near end was incredibly entertaining. The lighting was used both aesthetically and humorously to great effect, at one point descending from the roof of the theater to end dangerously close to the dancers. Like, a-foot-away close. The costumes included caps full of powder, which is released into the air upon slapping the top of the dancers’ heads. And of course, the prickly cacti make appearance. They are revered as idols, they are thrown to the floor, they are incorporated into a sculpture, they are used for dick jokes—everything you’d expect from a night at the ballet, right? But what could it mean? That’s for audience members to decide.

Alexander Ekman, the choreographer, said that he “had the chance to create a work with musicians in the studio…[with] a string quartet, we created a rhythmical game between dancers and musicians which became the score for the work.” The soundtrack to Cacti was that of a Zappa orchestral piece played ironically. With Beethoven and Schubert, the songs were anywhere from thoughtfully dissonant to remarkably upbeat and haphazard, like blasting classical movements whilst throwing china on the floor.

Alexander Ekman, the choreographer, said that he “had the chance to create a work with musicians in the studio…[with] a string quartet, we created a rhythmical game between dancers and musicians which became the score for the work.” The soundtrack to Cacti was that of a Zappa orchestral piece played ironically. With Beethoven and Schubert, the songs were anywhere from thoughtfully dissonant to remarkably upbeat and haphazard, like blasting classical movements whilst throwing china on the floor.

Standout performer roll call: Sarah-Gabrielle Ryan and Christian Poppe both provided the perfect canvas for the pre-recorded commentary. They managed to together perform the dance without acting out the narration exactly, or explicitly contradicting the narration. This gave the image of the narration being probably inaccurate, but possibly correct. The precarious nature of some of their movements was executed in a way that was engaging and played for laughs without becoming played out. Lucien Postlewaite at one point seems to be conducting the orchestra with his full body, giving himself over to the music with an expression of bliss and almost campy fluttering movements that would not be out of place in a ballerina’s performance of a fairy from the 1800s. His precision is masked by the spontaneous image he creates. A mark of a good dancer is making hard things look easy; hiding the calculations and micro-adjustments under a layer of grace and poise. Postlewaite nails this, drawing eyes and earning laughs even while the rest of the stage is in chaos.

Pacific Northwest Ballet’s ALL PREMIERE is showing this week Thursday-Saturday at 7pm and a matinee showing at 1pm on Sunday.