Hidden just across from QFC on the south end of Broadway is Steve Gilbert Studio. Visitors walk up the stairs and are greeted by a room of art under the sign “Wormhole Animism” before entering the main gallery, where Steve Gilbert himself–a Seattle-based photographer known for documenting the city’s Grunge scene in the 1990s–offers them a cup of tea, a glass of wine, or a good conversation. The gallery’s white walls display pieces made of copper, seaweed, moss, and electricity—Meghan Elizabeth Trainor’s work. As more people gather in the room, she prepares for her artist talk, a conversation that will tell the story behind her show “Wormhole Animism” and the significance of her art. Gilbert and Trainor have been friends for “a very long time,” she says, “but I don’t wanna say exactly how long for both of us,” Trainor laughs.

With a background in new media, Trainor questioned how to proceed in the world of art and technology amidst the hostile cultures of sexism, capitalism, and environmental depletion. For her, the logical thing to do was obvious: rebuild the entire history of technology to suit the worldview that is needed—now more than ever—to sustain life.

Her narrative starts before the European Age of Enlightenment, portrayed in her essay “Familiar Algorithm,” explaining why technological development was “handed over to men” and how that relates to witches, traveling to the moon, “and things like that.” Trainor shares that the work she’s done for the last decade is built on material evidence of the “fictional speculative space” that she created. “Over the years, the realization has come about that that world is not particularly speculative,” Trainor says, “It is simply what has happened when you erase people from history,” referring specifically to the work of women in technology.

“Wormhole Animism” mysteriously tells the story of “a very particular kind of person, from a very particular place in history, that is primarily white folks from Europe.” The reason she focuses on that group, Trainor says, is because she belongs to it. While “staying in her lane,” she hopes that her work holds open doors for parallel narratives. Her art points to other references, like the thousands-of-years-old context of the binary system, which “certainly does not start in Europe.”

From there, Trainor, like speaking of an old friend, mentions the influence of Johannes Kepler in her work. Known as the grandfather of astrophysics, what is less known about the physicist is his significance in early science fiction. His mother, Katharina, was a witch. She was persecuted for witchcraft, which “stopped [Kepler’s] life for him to go fight against it, to make sure [Katharina] wasn’t killed for practicing witchcraft,” Trainor says. From this, Kepler wrote “The Dream,” a book considered one of the earliest documented works of science fiction.

In a narrative about a little boy and his mother, Kepler tells a detailed story of what it might be like to travel through the atmosphere between Earth and the moon. The way the characters achieve such travels is through the assistance of a demon (Daemon, a helper in Greek mythology). “It’s interesting how that term gets turned into something evil by the European church,” Trainor suggests. She expressed that the merging of fantasy and science in “The Dream” was of great inspiration to her own process. “I pulled from that interesting relationship between the father of a scientific field and his insistence on the ‘witch’ point of view, and the ‘witch’ goal of getting to the moon.”

With this, her narrative grows. Ancient pagan practitioners in Europe were exposed to logic, which interrupted their “magical abilities,” Trainor says. While several parallels form in my mind, she continues, “If you’re steeped in logic, rationality, and purism, you can’t do things like [magic], right? I think just psychologically, there’s a cut.” The severing of the “magical” thinking pathway is the reason that early medieval witches launched into technology, she adds, saying that the empiricist mindset led them “to have to go forward through tech,” by designing new systems, losing their relationship with their animal familiars, and “building robotic familiars, which sounds fantastical until you look at how far back that culture goes.”

“What NASA was doing in the 50’s and 60’s,” she comments, “they were doing [back then]. But then we have the witch trials, which kind of disrupts everybody’s ability to be alive.” According to the artist, the logic that followed was transferring technological knowledge to alchemists, mostly men, who “get left alone, and have a lot of resources,” allowing them to sustain research under the guidance of witches. Fast forwarding to Alan Turing and Bletchley Park, during WWII, “Most of the people working at Bletchley Park were women,” Trainor points out. “Programming was women’s work. It was seen as a kind of drudgery actually, up until the 70’s,” and statistically, “a bunch of these [women] were witches,” she completes, saying that this shows a point of “conspiracy of witches who had been pushing for travel to the moon since the eighth century or so.”

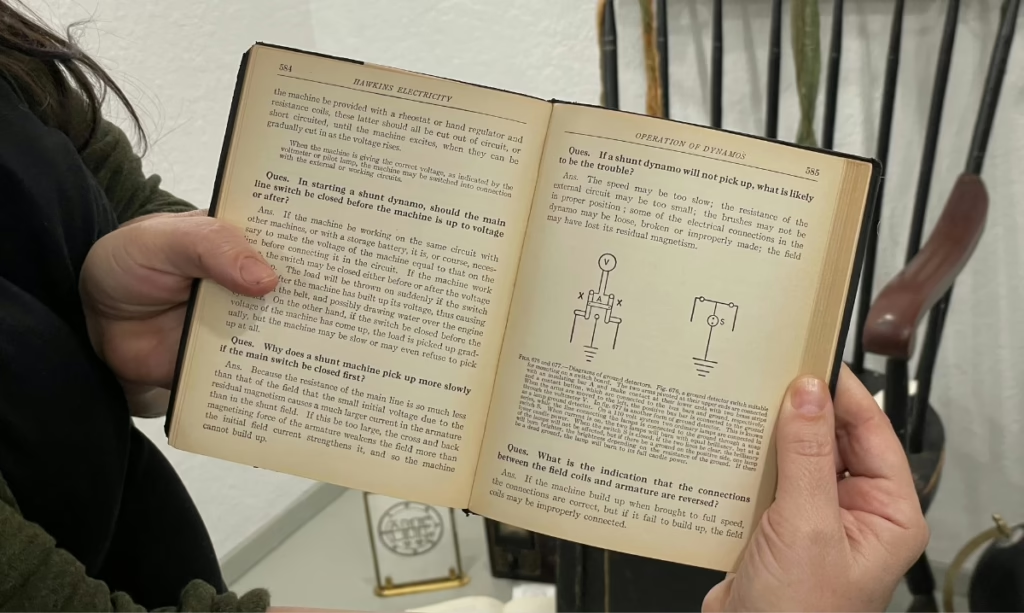

Trainor’s narrative seeks cultural overlaps between witchcraft and science and technology, addressing the split that came with the Enlightenment. She illustrates this with the quote, “Let us not confuse zero with stillness,” from her namesake show at CoCA, in 2021. The phrase underlines a magical way of thinking about electricity instead of picturing computer code as zeros and ones through the “false metaphor” that machines can understand it. “The machine doesn’t get zeros and ones, it doesn’t get on and off, what it gets is electrons flowing through wires; either they’re moving, or they’re still,” she explained. Stillness is a different way of perceiving the value of zero—“It’s not empty, it’s still,” Trainor said to an audience so rapt that I thought I could hear the stillness of my subatomic particles.

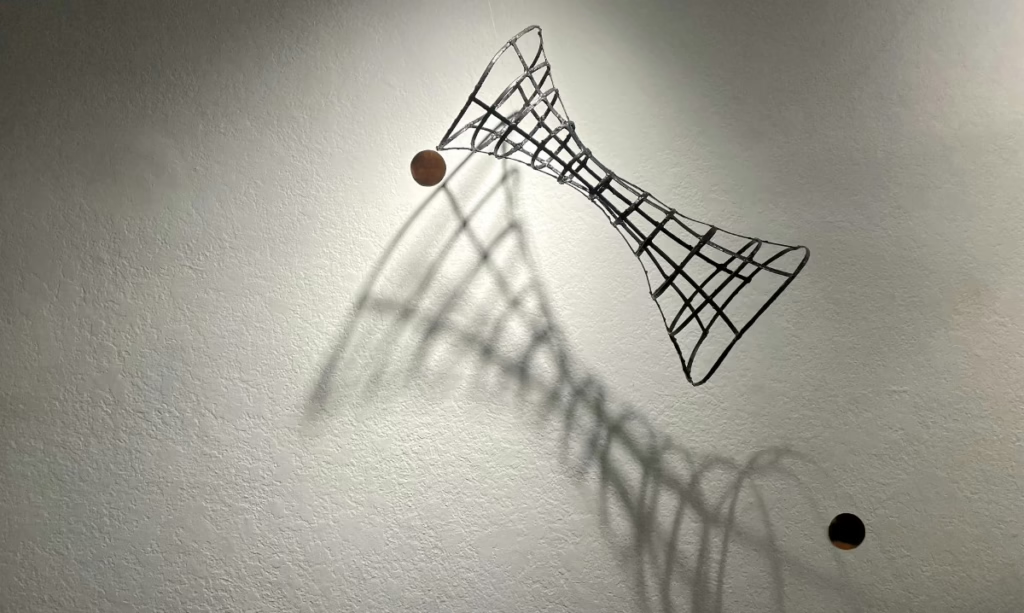

Though focused on electricity and technology, Trainor’s work “isn’t high-tech,” she notes, pointing to a piece on the wall behind her: two funnel-shaped seaweed structures, bound by red electric wires, that spin around attempting to align—but never do so. “It’s a very earthy, natural way of engaging, which I think is important for us as members of late capitalism,” she says, pointing out that nowadays, our experiences of technology are mediated by the industry, “They’re closed off. We can’t engage with them,” noting how dealing with an iPhone, for example, is so different from “an old Ford where you can open up the engine.” I thought of my father, who owned a computer shop in Brazil in the 1990s and brought home old parts from broken mice for me to play with as a little kid. Now, I can’t recall the last time I used anything other than a touchpad to navigate a computer.

Building onto her magical interpretation of technology, Trainor tells us that one of the first things that is commonly done in magical practice is to “make a sacred space” by creating a circle. In turn, anytime a circuit is flipped on, electrons are sent from stillness into movement, “you’re creating a circle,” she compares. More than that, the presence of crystals is also common to both spiritual practices and technology, “Any kind of computer, your phone, anything, there’s a quartz crystal at the center of [it]; it’s the oscillator,” a component that acts as a timer, sending signals for the computer’s activities, in a role just as symbolic as using quartz as a mediator of energy during a tarot reading. “So you’ve got a quartz crystal with electrons in a circle going around through copper, right? And if that’s not magic, I don’t know what it is.”

Reorienting people’s relationship to the materials, systems, and mechanisms that make up the technology around us through the lens “not of consumerism, but of a spiritual practice” is what Trainor references in her exhibit’s title. It’s about listening to the things around us, “not just other humans,” she reveals, “but to the animals, the rocks, the minerals, the space.” Being in community with them, rather than “sitting inside of a hierarchy.” This is the one thing Trainor wants people to take away from her work.

Before opening the conversation to questions from a—perhaps literally–spellbound audience, Trainor specified the motives behind each of her artworks in “Wormhole Animism.” “We are full of quantum particles; we have this macro-micro happening. That’s what we’re made of below everything: the cells in our body, the molecules, the quarks.”

Mentioning black holes and white holes, the Einstein-Rosen bridge, gravity, subatomic particles, the fabric of space-time, and gouache paint, Trainor closed her talk by returning to an ancient concept that fascinates humans, that many times leads us to envision, create, and keep works of art: beauty. “Black holes are incredibly violent, massive systems. And yet, their parallel sits inside us at a scale that we don’t even have numbers for in our brains. There’s a huge beauty in that.”

Sophia is an internationally published author with her book Primeira Pessoa, as well as a young classical singer. Born and raised in Brazil, she believes the greatest role of a writer is to bring forth the truth, the honesty, and the humanity that echoes within each one of us.

Be First to Comment