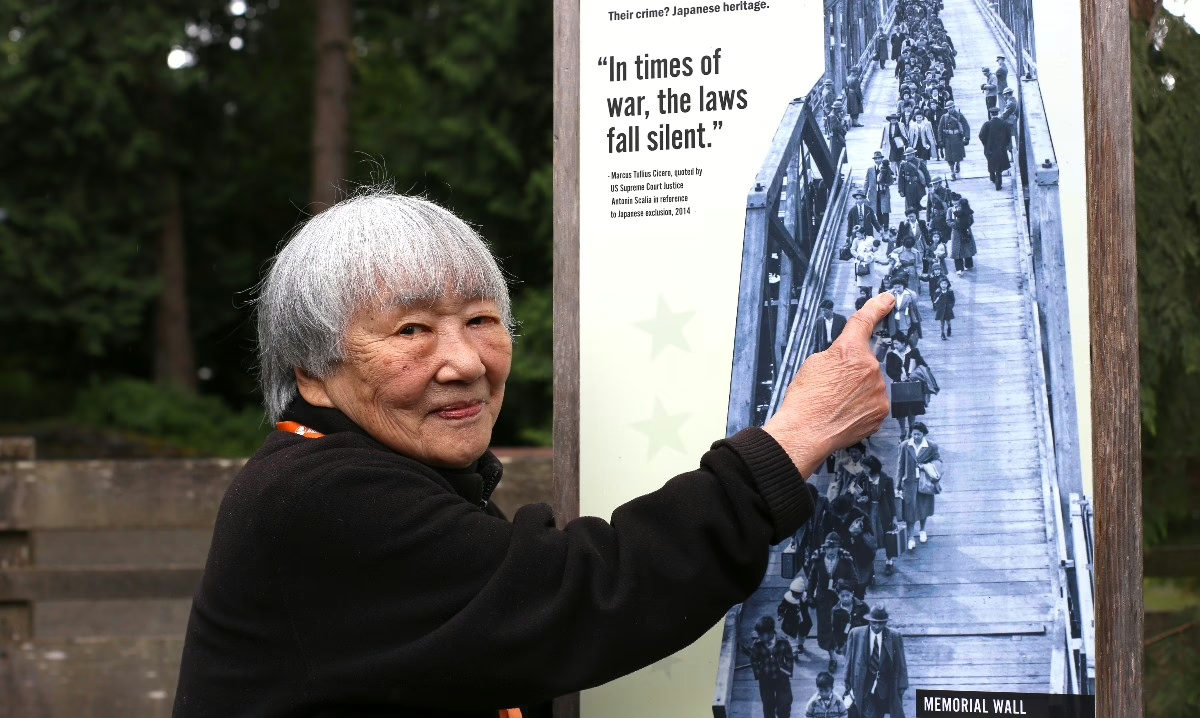

Curiosity about a historical photograph in Seattle’s International District led me to the former Eagledale ferry dock on Bainbridge Island, home to the Japanese American Exclusion Memorial. Even though the arrival of Lilly Yuriko Kodama at the memorial turned out to be an unexpected encounter, it became the best place and time to meet her.

To my surprise, Kodama looked at the photograph and said, “This is my aunt Fumiko Hayashida and her daughter.” I had already started to see so many connections with it since I had seen a single photograph from a tiny alley.

I had recently started to look closely at Japanese American history in the United States as I was working on a project for a Cultural Anthropology class at Seattle Central College. Accordingly, my journey toward Bainbridge began with seeing a mural with that heart-rending photograph of a woman cradling a baby in Nihonmachi Alley in Seattle’s International District.

The text on the mural identified her as Fumiko Hayashida and provided a summary behind the picture. The original photograph was taken on March 30, 1942, by a staff photographer who was attached to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer near the ferry dock on Bainbridge Island. Later, the picture was republished and reproduced in many different forms around the world. Since 1976, the negative has been preserved at the Museum of History and Industry (MOHAI), and later, the staff there identified Fumiko Hayashida and her daughter by enlarging the photo and reading the tags they had worn.

However, the faces in the photograph forced me to look more closely at the story behind it. I saw Hayashida again at the Wing Luke Museum in Seattle. A copy of the iconic photograph, the actual purse she holds in the photo, and the hotplate she used in the concentration camps were in the collection there.

Seeing again and again hundreds of re-publications and reproductions of Hayashida’s photograph and its connections reminds me of Steve McCurry’s famous “Afghan Girl” photographs from the 1985 cover of National Geographic. These single faces represent the entire population and the tragedies they had to go through.

After going through libraries, museums, and so many online archives and references, I finally decided to see the exact historical point in Bainbridge Island where some of the most popular historical photographs, including Hayashida’s photo, had been captured in that historical phenomenon. The place where their families were forcibly removed for an uncertain journey, the place where they left behind their houses, farms, businesses, and familiar lifestyles.

Even though meeting Kodama at the historical point was coincidental, I was tempted to speak to her because her face was familiar. Of course, she was in my prior online search during searches for iconic pictures. What I didn’t know was that she was with her family and relations as a child in some historical photos I already collected through this journey. “This is me with the birds in my hair and my mom and siblings. We all were holding one toy that my mom said we could bring,” pointing to a photograph, she says.

She also pointed to the symbolic photograph, which I saw everywhere along my journey, saying she was her mother’s youngest sister, Fumiko Hayashida. “I saw my aunties, my cousins, and then the entire Japanese community here. That was the only time we had a big gathering like that. So, I thought this was a big celebration day.”

The memories and symbols are still everywhere of how Japanese Americans in Seattle and the Bainbridge area dealt with the tragedy of forcible removal with only six days’ notice. During the World War II era, after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, calling for the exclusion of all civilians of Japanese descent from designated military areas.

Japanese Americans who lived on Bainbridge Island were the first group in the country to be removed from their homes by the federal government, as they were considered a threat to the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard on the Kitsap Peninsula. Including Hayashida, Kodama, and their families, more than 9,000, both Alien and non-alien Japanese people who lived in the Pacific Northwest, were forced into incarceration until March 1946.

Left to right: Shigeko Kitamoto, Tomiko Hayashida, Yuriko Kitamoto, Fumiko Hayashida, Hideko Kitamoto, Grandma Tomie Nishinaka, Hiroshi Hayashida (baby), Yasuko Hayashida (in lap), Nobuko Hayashida, Hisako Hayashida, Ichiro Hayashida. At the Kitamoto family home on Bainbridge Island, WA. Photo credit: BIJAC

“Well, I was seven, and I had no idea there was a war,” Kodama, who is now 89, recalls the experiences they had when she was a 7-year-old in 1942 during the removal of Japanese Americans to internment camps. “My mother said we would take the ferry to Seattle tomorrow and then go to Disneyland. I was so excited. I couldn’t sleep.”

They were only allowed to bring what they carried or wore; they dressed up with their best and heavy clothes and filled their luggage with essential things. The Japanese Americans in Bainbridge were the first group removed to the Manzanar concentration camp in California, and later, most of them were sent to the Minidoka concentration camp in Idaho.

The Former Eagledale ferry dock on Bainbridge Island later became a National historic site that is home to the Japanese American Exclusion Memorial. The hundreds of names on the memory wall remind the children, women, and men who were stepping on the departure journey to the unfinished barracks in the California desert in 1942. “That’s our family,” Kodama pointed toward the memory wall.

The memorial site forces me to compare the pictures I saw in the archive collections. It reminds us of the faces of children, women, and men who were well-dressed and stepped onto the ferry for an unknown departure. The memorial reminds us that it is not something easily erased by time.

Once World War II ended, over half of Japanese Americans arrived back to their homes on Bainbridge Island, but they were faced with many challenges when settling back there. Fumiko Hayashida, the woman behind the symbolic picture, died in 2014. However, her picture and the productions around her still represent the historical phenomenon that the Japanese-American community faced in the past.

Symbols of hurtful history are standing around us, iconic pictures surround us, and voices of memories speak to us. Everything and everyone whispers to us again and again that ‘Nidoto Nai Yoni’ – ‘Let It Not Happen Again’.

Indunil Usgoda Arachchi is from Sri Lanka and has worked for several years as a newspaper journalist and freelance photojournalist for local and international media. After becoming a student at Seattle Central College, she joined The Seattle Collegian.

A very poignant series of photos to remind us of the humanity of people conflicted with issues of our world.

Thank you!

Gary S