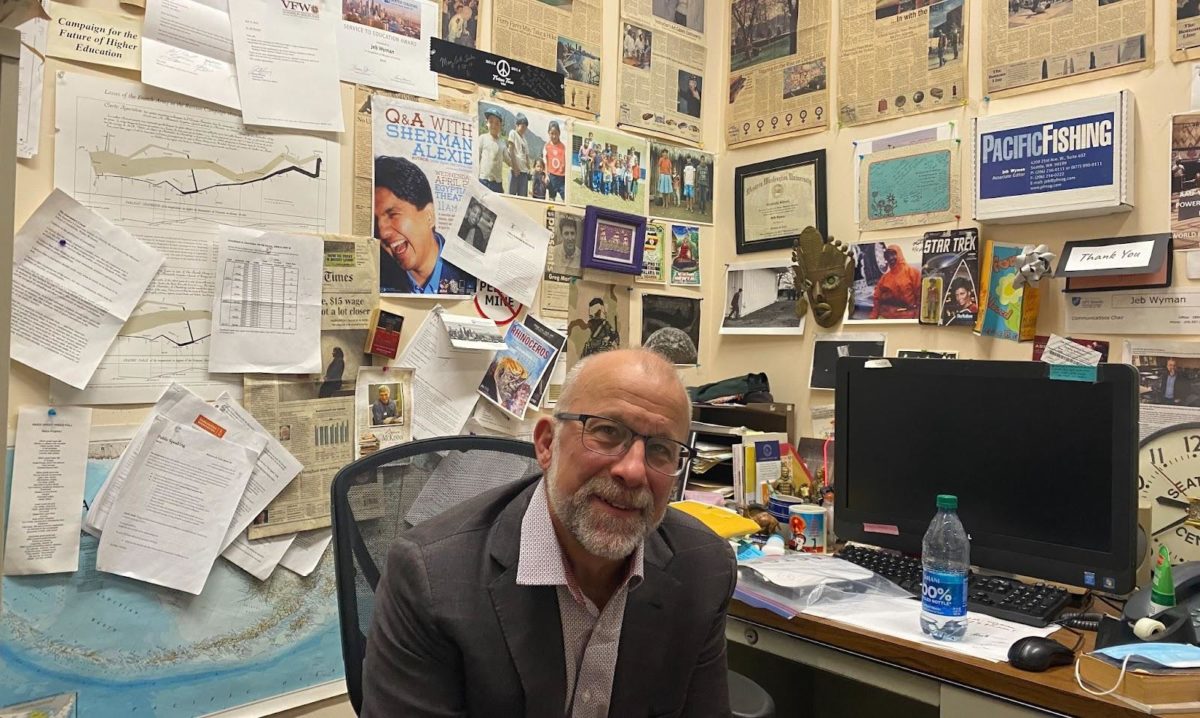

Jeb Wyman: Flawed, Fortunate, and Fully Human

Housing yellowed newspapers, stacked books, eclectic dusty objects, and gifts from students, Jeb Wyman’s office displays his 30 years of teaching and is perhaps a reflection of himself—flawed, fortunate, and fully human.

A Naive State

Wyman grew up in central Wisconsin on an 80-acre farm; his childhood was tranquil, simple, and easy — “I felt that I grew up in a state that is kind of naive,” he said.

Having been brought up in a place he described as “one of the least diverse places in the country,” where there were virtually no people of color, Wyman accepted prejudice without question.

“Normal, good people.” That was how he would see himself and those around him, despite unconsciously holding ideas about people who did not look like him and making jokes about what he said “would be considered awful today.”

Growing up, he did not know the world was any other way, and he did not question it.

Over his lifetime, Wyman has been glad to see the country “get better consciousness about bias, prejudice, and race; there have been great tragedies along the way that have helped penetrate people’s ignorance and open their eyes up.”

Flaws and All

Looking back, Wyman describes his younger self as narrow, provincial, foolish, and irresponsible.

“[An] immature young person, who had no idea about what really mattered in life…having basically everything I needed, whenever I wanted it,” he said.

As a young man, Wyman says he did not know his privilege and good fortune in getting an education. Wyman attended the University of Wisconsin Madison, an enormous institution with over 40,000 students

“I had been a big fish in a very little pond. Then I went, and I was a tiny little minnow in a huge ocean,” Wyman reflected upon a state of naïveté and ignorance he once lived.

Good Fortune

Reflecting upon his life, Wyman says, “In the larger schemes of life and the arc of life, I still believe that so much of the journey we take…is really capricious,” and “there are curious and marvelous accidents that happened: chance meetings, little conversations, little things.”

In a nutshell: A poster, a conversation, a career in Alaska, a critical 10 minutes, and eventually, a family.

A poster—A speed reading class advertisement prompted Wyman to attend, driven by the belief that improving his reading speed would enhance his academic performance.

A conversation—In walks late, a girl. She briefly sits and leaves, realizing the class was a scam. Very uncharacteristically, Wyman followed her out of that room and struck up a conversation. He learned she had gone to Alaska and worked on a fishing boat the summer before, and he decided he had to do the same.

A career in Alaska—The following summer, in 1985, Wyman drove in a rusted Volkswagen from Wisconsin to Anchorage, Alaska. After selling the old car for $150, he got tickets to fly out to Bristol Bay and secured a job on a fishing boat.

A critical 10 minutes—With aspirations of owning a boat and needing money, Wyman went to Dutch Harbor. It was November, cold and rainy. He walked down the pier, going from boat to boat, but no one was there. Getting somewhat discouraged, he went to a cafe to warm up. After wasting hour after hour, he decided to go back outside. A while later, after visiting empty boat after empty boat, there was a boat with two guys.

“I am certain that [if I had] walked by that boat 10 minutes later or 10 minutes before, those guys would not have been on the deck…But as it was, I ended up getting a job on that boat,” Wyman said.

A family—Working on the crab boat for five months, Wyman formed a deep friendship with Bob, a chief engineer, who took him under his wing. In 1991, Bob invited Wyman to stay with him in Seattle, and he set Wyman up on a date with one of his wife’s friends. In December 1993, they married and soon welcomed two sons into their family.

A Crazy Lucky Life

“[A] deep belief right now, about my life, is that I’ve had this crazy lucky life,” Wyman said.

A considerable part of that life, he says, is teaching at Seattle Central and having thousands of students teach him about life, dignity, grit, and having dreams. He calls his experience teaching “cumulative lessons from the students about what it means to be a human being.”

Wyman greatly values having spent 30 years in classrooms. “It has been priceless. What I learned in school is nothing compared to what the students have taught me over the years.”

Sincerely, Wyman considers it “a great privilege…to be present at this point in people’s lives as they are building their future and are about to light their rockets and take off.”

Telling Stories

Wyman cherishes his role as an English teacher mainly because it allows him to read the stories of his students.

He firmly believes “storytelling is a way to communicate ideas and have conversations about ideas.”

Over the years, he has grown increasingly personal in his teaching approach, embracing sharing his own stories with his students. Initially, he had not considered sharing his stories the teacher’s role, but each year, he became more open and vulnerable.

In the past decade, Wyman’s focus has extended to veterans’ experience. He and his colleagues have welcomed veterans into their classrooms. As an English teacher, he began to receive honest, authentic stories from these veterans, stories that did not glorify heroism but sought to understand the true meaning of their experiences. This led him to initiate a project to gather and eventually publish the true stories of veterans in his book “What They Signed Up For.”

Wyman realized that stories are key to engaging the human heart. Whether through written or spoken words, stories allow people to immerse themselves imaginatively in the world being conveyed or expressed, creating a connection with one another.

Feeling Vulnerable

Wyman has often felt vulnerable in the classroom, especially when confronted with situations or questions he does not have the knowledge and the tools to address.

“[It took me] many years to remove my own ego out of these encounters, which I think is part of the growth…to realize this is not about you, it’s about the students. You don’t have to be right as the teacher; you can be wrong.”

Making People Upset

From 2003 to 2008, Wyman served as an advisor to the City Collegian, the college newspaper.

“It was an extraordinary time in my life…It was a wild roller coaster experience,” he said.

He said the students continually put out articles that created all types of feedback. Notably, some stories would provoke strong emotions and unsettle readers, particularly the college administration.

Wyman never truly became accustomed to the idea of upsetting people, but he remained committed to ensuring that it was justified.

“I resigned as the advisor, and the administration immediately changed the locks on the newsroom, and shut down the paper.” Since then, “I have had to live with the knowledge that if I did not resign, that would not have happened. The City Collegian, which was at that time, 42 years old…ended because of a decision I made.”

That, he said, was one of the most challenging experiences during his time at Seattle Central.

A Lasting Legacy

For teachers like Wyman, teaching is a sacred opportunity and a great privilege, and leaving a lasting mark takes on a profound meaning.

“The thing about teaching is — and all of my colleagues will say the same — you meet people on the first day of the class, and over the entire course of the quarter, you form these strong bonds. You watch people go through a really powerful experience, individually as students. There is a lot of motion, there is a lot of sweat, sometimes there are tears… And the quarter ends, and you say goodbye to each other. For the great majority of the time, students go off into their futures, and you don’t get to know what happens in their lives. You don’t really know if you had an impact on them at all or even if they remember you years down the road.”

But now and then, Wyman gets an email.

“It doesn’t happen often; you get someone that, in fact, you seem to have had the privilege of making a difference. That’s part of our intangible, invisible, and utterly precious legacy that all of us teachers have. You have to have faith. You don’t really get to know that you’ve made an impact…which may be a good lesson for life because a whole lot of life is based on a belief, a belief in what you’re doing…It’s not like an exchange of money, you don’t know the goodness you’ve done.”

Danika is an aspiring journalist based in Seattle. Born and raised in Jakarta, she has long been drawn to the gravity of stories—the way they hold what might otherwise slip through the day. As editor-in-chief, she approaches her work with curiosity more than certainty, trusting small details to reveal larger truths. For her, storytelling is less about control than attention: a practice of listening closely and noticing what remains after the noise.

Thank you for an in depth article that highlights how our experiences play such an important part in molding us and providing direction in our lives if we are open to it! If so, we always have the opportunity to continue to grow throughout life as we move towards becoming our BEST self!

Congratulations!