Walking the AIDS Memorial Pathway

Under the low, slate-gray sky of a Seattle winter, the Capitol Hill Station plaza vibrates with perpetual motion. Commuters funnel between light rail, buses, and the bustle of Broadway, head-down in a space defined by the transient logic of transit.

But a geography of loss slices through that flow. Steel, glass, and concrete anchor a heavy history to the pavement here, where the AIDS Memorial Pathway—known as the AMP—claims the ground.

Completed in 2022 at the intersection of Cal Anderson Park and the regional transit hub, the AMP does not simply mark the impact of HIV and AIDS on King County. It consecrates Capitol Hill, the historic heart of the city’s LGBTQ+ community, as the epicenter of an epidemic that redefined a generation.

“Ribbon of Light”

Horatio Hung-Yan Law’s “Ribbon of Light” traces the northeast edge of Cal Anderson Park. Three laminated glass structures rise from the damp landscaping. Translucent and teal, they mimic the color of deep water or a vein pulsing beneath pale skin. Law designed these forms to represent pieces of the sky that shattered and fell to earth.

The sculptures do not merely decorate; they testify. They function as public park features while serving as solemn markers for the thousands of King County residents who died of AIDS-related complications. Planners chose this location with intent, embedding the memorial into the dense, living fabric of Capitol Hill rather than exiling it to the quiet corner of a remote cemetery.

Documenting the unknown

To understand the weight of the art, observers must confront the history it obscures. While the calendar reads 2025, the ground here holds the static charge of November 1982.

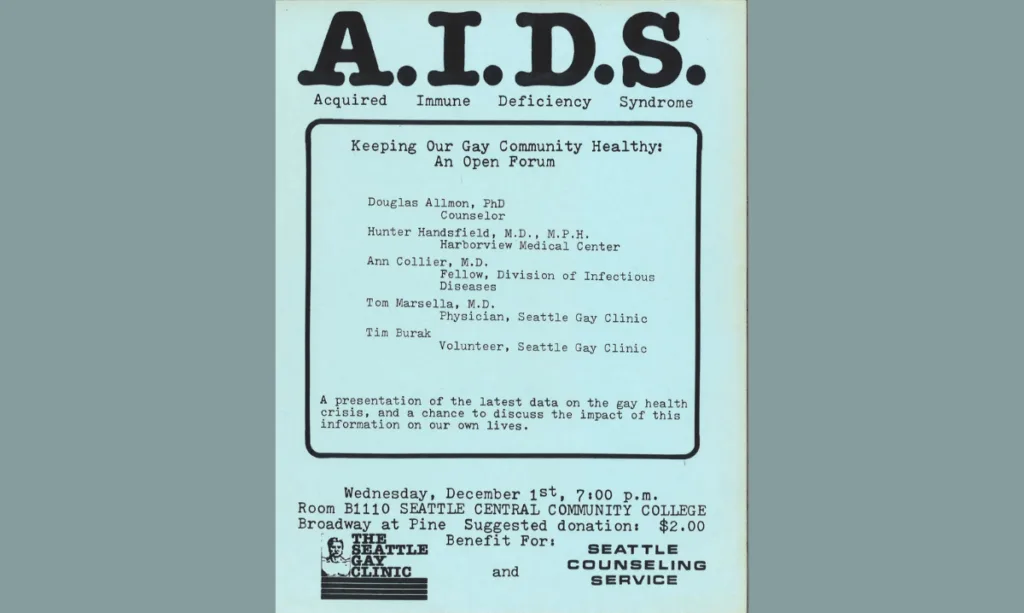

That month, King County officials reported the first local case of what medical professionals would later call AIDS. In those early days, the virus was less a diagnosis than a terrifying mystery. Artifacts from this era, preserved in the King County Archives, reveal the stark simplicity of the early response.

A sheet of blue paper from 1982 survives. It advertises a community forum, asking residents to enter a room to listen to doctors discuss a killer virus.

The typography conveys urgency, stripped of sentiment. In 1982, information was a commodity as scarce as hope. A flyer stapled to a telephone pole on Broadway or Pike Street often served as the only line of defense between a community and the unknown.

“We’re Already Here”

Across three locations in the plaza and park, the art collective Civilization interrupts the open space with “We’re Already Here.” These metal and concrete silhouettes translate the ephemeral language of protest signs into permanent fixtures, standing rigid against the wind.

The debossed typography casts long, shifting shadows. As the sun moves, the shadows lengthen like monuments in their own right, evoking historic moments of public convergence: vigils, marches, and demonstrations.

The collective derived the title from a 1990 declaration by activist Brian Day. Standing before a megaphone in Madison Valley, facing neighbors terrified of a proposed AIDS care center, Day declared, “We’re already here.”

The signs halt the liquid movement of the plaza. They fossilize a rage once deemed disposable. While commuters flow around them, the signs remain fixed, insisting on the presence of those who fought for visibility when the prevailing political winds favored erasure.

The logistics of care

The archive connects inextricably to the asphalt. While the protest signs publicize the crisis, the history of Seattle’s response was written in domestic spaces.

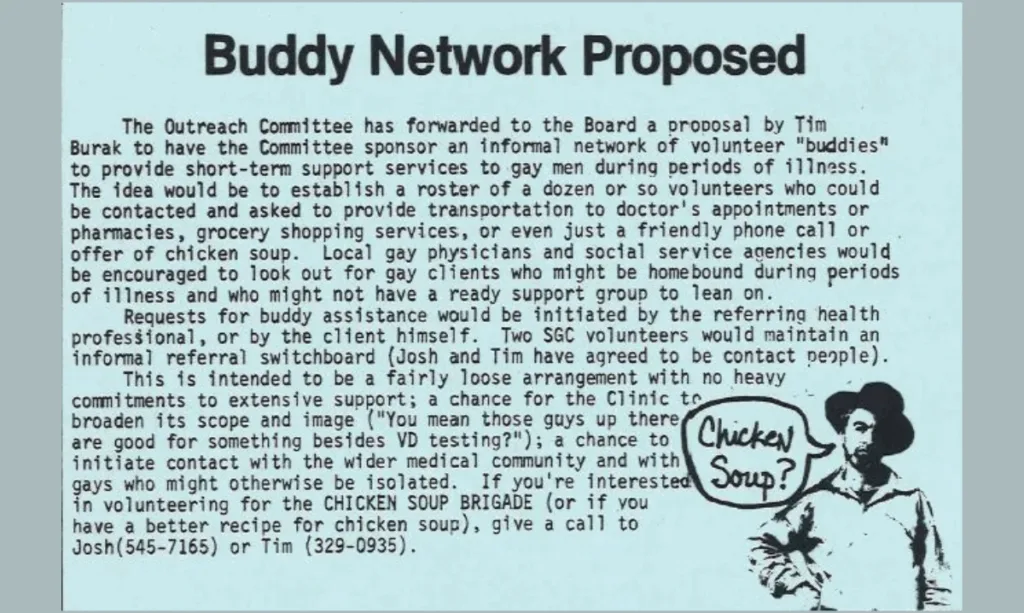

Volunteers formed the Chicken Soup Brigade in 1983. This was a logistics operation born of necessity. Tim Burak and a cadre of volunteers founded the organization because men were starving in their apartments. They required grocery lists, transportation, and basic care rather than sculptures or plaques.

Archival materials detail the practical nature of this compassion. A flyer titled “Buddy Network Proposed” features a rough illustration and a call to arms involving food rather than weapons. The AMP memorializes this humble texture of history: the smell of soup in a hallway where someone lay dying, and the sight of volunteers driving station wagons to deliver meals to neighbors too weak to boil water.

A portal of silence

Christopher Paul Jordan’s towering sculpture, “andimgonnamisseverybody,” dominates the plaza center.

Stacks of speakers build a 20-foot-tall X. Jordan describes the X as a “positive sign on its side,” a symbol representing the intersection of love, banishment, and the unknown.

The work invokes the Dikenga, a Black Indigenous spiritual mark of the afterlife, representing a crossroads between the physical and spiritual realms. Standing in the flat light of a Seattle afternoon, the speakers maintain an eternal silence. They signal a foreclosure on the future—a monument to lost voices and the music that simply stopped.

The arithmetic of survival

Relentless numbers define this history. King County recorded seven new cases in 1983. The year 1984 brought 52 new cases and 18 deaths. By 1996—the year effective antiretroviral therapies began to bend the epidemic’s trajectory—the county recorded 493 new cases and a cumulative total of 3,164 deaths.

The AMP visualizes these losses through the “Names Tree,” an augmented reality experience. Visitors pointing a smartphone at the northwest corner of the park, near an old Chinese scholar tree, watch the branches transform. Lighted leaves ascend into a digital sky, resembling lanterns or souls. An audio roll call speaks the names of the dead, a litany that feels interminable.

Restoring the narrative

Nearby, in the Station House building, artist Storme Webber’s installation “In This Way We Loved One Another” remediates the historical record.

While blue flyers and government statistics tell part of the story, Webber’s work restores the narratives often bleached from mainstream accounts: the experiences of the working class, people of color, healers, and witnesses. The artwork, visible through the building’s windows, features photographs of faces looking directly at the viewer.

Webber portrays these subjects as people who found joy and community while walking through the fire. The work reminds the city that the crisis hit marginalized communities with specific ferocity, and those communities responded with specific forms of resilience.

A disruption in the commute

World AIDS Day, observed annually on Dec. 1, brings a temporary focus to this history. However, the AMP serves as a stark reminder that the epidemic is not merely a closed chapter in a history book.

While medical advancements have transformed HIV into a manageable chronic condition for many, the virus continues to circulate. King County health officials still report new infections, and deep disparities in access to care persist. The memorial underscores a difficult truth: while the dying has slowed, the transmission has not stopped. The site stands as a testament to those lost, but also as a warning that the work remains unfinished.

Memory disrupts the commute. It creates a deliberate collision between the 5 p.m. rush, the ghosts of the past, and the reality of the present. The memorial refuses to pause the world; it forces the history of the epidemic into the aggressive flow of the living.

The glass sculptures stand. The speakers loom. The words debossed into the metal wait for readers. For the pedestrian rushing to the light rail, stopping to read is an act of disobedience against the city’s imperative to keep moving. In this plaza, remembering becomes the act, and persistence becomes the work.

Danika is an aspiring journalist based in Seattle. Born and raised in Jakarta, she has long been drawn to the gravity of stories—the way they hold what might otherwise slip through the day. As editor-in-chief, she approaches her work with curiosity more than certainty, trusting small details to reveal larger truths. For her, storytelling is less about control than attention: a practice of listening closely and noticing what remains after the noise.