The gown Queen Marie of Romania wore to the 1896 coronation of her cousins Tsar Nicholas II and Tsarina Alexandra of Russia; more than 80 works by Auguste Rodin; nine sets of post-World War II French haute couture fashion on toddler-sized dolls; a full-sized replica of Stonehenge… What in the Sam Hill are all these things doing in a rural town in Washington state?

Goldendale, Washington, is home to a population of just over 3,400 people and a remarkably random collection of artworks at the Maryhill Museum of Art —“one of the Northwest’s strangest cultural institutions,” as Portland Monthly puts it.

Like a flea market curated by a well-traveled millionaire, the collection includes Rodin’s bronzes and plaster studies, an array of Native American baskets, Art Deco glass pieces, 400 chess sets, Queen Marie’s memorabilia, Orthodox Christian icons, baby-sized vintage French designer clothes, and more. Though it may seem difficult to trace even a loose connection between all these pieces, they actually tell an oddly cohesive story.

It all started with Sam Hill himself—though the origins of the expression “Sam Hill” have other possible referents. Samuel Hill, an American businessman born in 1857, built the structure as a mansion for himself, his wife, and his daughter, for whom the museum was named. The home was later dedicated to house a public museum for the “betterment of French art in the far Northwest of America,” Hill wrote in a letter in 1917.

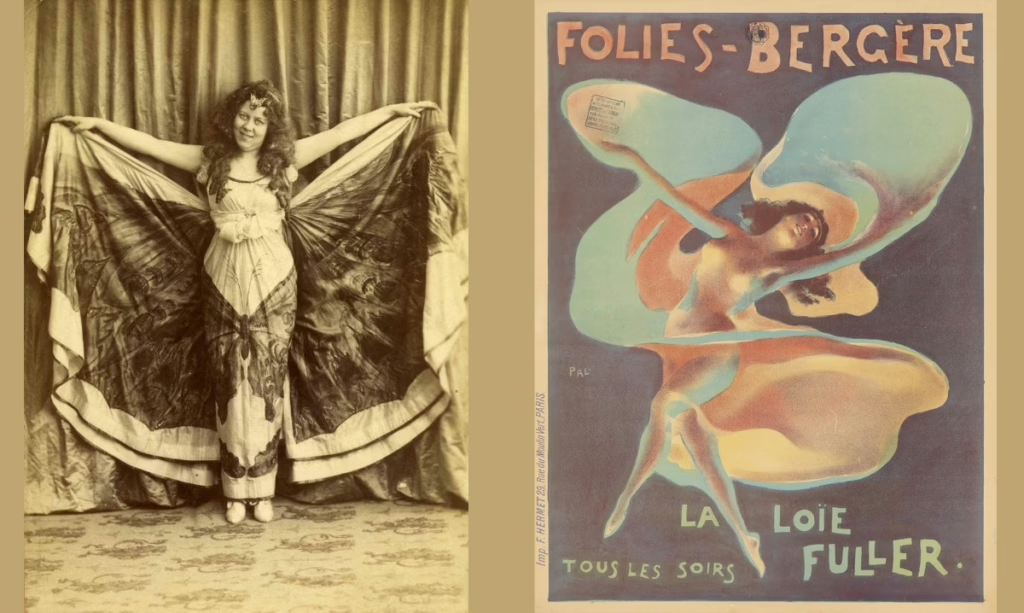

Growing up in Minnesota, Hill became a wealthy railroad executive and was soon drawn by Seattle’s business potential. He merged two gas companies into Seattle Gas and Electric, supplying gas to the city. Hill left the gas business in 1904 and moved on to fund other ventures, including the mansion in Goldendale. Nearly a decade later, Hill’s decision to turn the unfinished house into a museum was influenced by Loïe Fuller, an American pioneer of modern dance living in Paris and a close friend of Hill’s.

Now, where did the museum’s enigmatic collection come from?

Some of it came from Hill’s art collection, personal items, photos, and mementos from the Good Roads Movement, as well as articles acquired during his travels. But the bulk of the museum’s selection came through three female figures in Hill’s life: Loïe Fuller, whose relationships with well-known artists in France contributed to the core of the museum’s collection; Queen Marie of Romania, a close friend of Hill’s who donated her royal regalia, furniture, and paintings to Maryhill; and Alma de Bretteville Spreckels—”Big Alma,” also known as the “Great Grandmother of San Francisco”—who had worked with Hill on cultural projects in California and donated pieces from her personal collection, including some of Auguste Rodin’s works.

The Stonehenge replica, however, was Hill’s idea. Erected in 1918 as a monument to those who died in service during World War I, it became the nation’s first WWI memorial, commemorating 17 soldiers from Klickitat County, WA. Hill believed, though erroneously, that the original Stonehenge was built as a place of human sacrifice, tracing a parallel between lives lost at war and ancient rituals— an allegory for the human condition in the backdrop of 19th-century America.

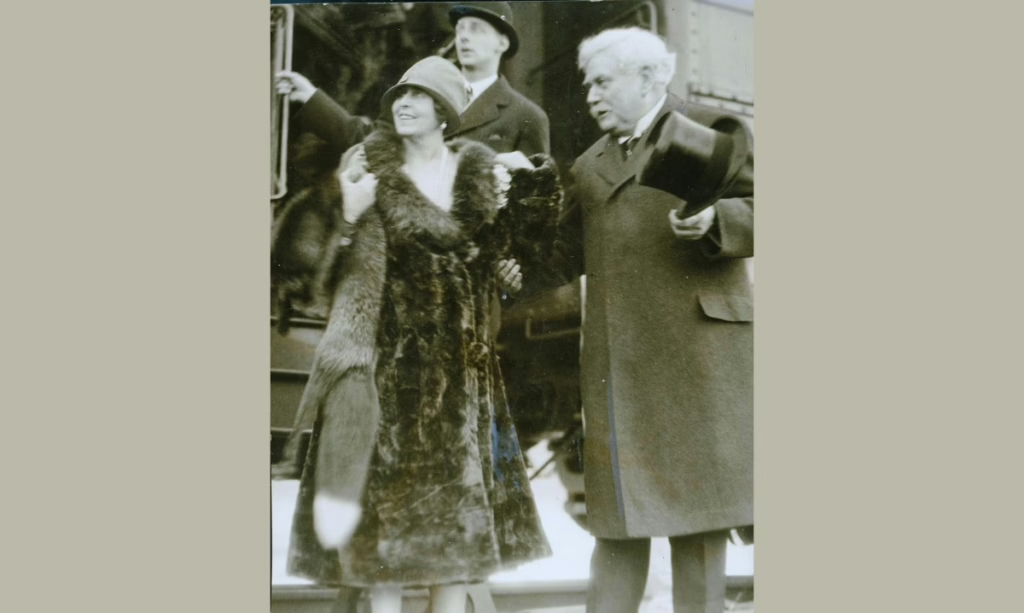

In 1926, Queen Marie, invited by Fuller, traveled to the United States for the first time to dedicate Maryhill—though at the time, it was still an unfinished structure—in a ceremonial acknowledgment of the museum’s purpose and significance, while also donating $1.5 million worth of her personal art collection and belongings to Maryhill. Her visit “dominated newspaper headlines” in the U.S., according to The New York Times, whose reporters attended her dedication speech on Nov. 13, along with a crowd of 2,000 people.

During her travels, the queen wrote in her personal journal, “I knew when I set out that morning to consecrate that queer freak of a building that no one would understand why; I knew it was empty and in no wise ready to house objects for a museum.” Despite acknowledging that the structure itself was unfinished and that Hill’s idea was unconventional, she completed,

“I knew that a dream had been built into this house, a dream beyond the everyday comprehension of the everyday man.” It was in this tone that the monarch conducted her dedication speech, referring to Hill as a friend, “He is not only a dreamer, but he is a worker,” she said, capturing Hill’s visionary—and industrious—spirit.

Samuel Hill died in 1931 in Portland, Oregon, with the museum still unfinished. His ashes were placed near the Stonehenge memorial. Hill’s glamorous dream of a cultural institution, however, did come to life when the museum finally opened its doors in 1940.

The Maryhill Museum of Art remains alive and open to the public, featuring its permanent collection and rotating exhibits.

Sophia is an internationally published author with her book Primeira Pessoa, as well as a young classical singer. Born and raised in Brazil, she believes the greatest role of a writer is to bring forth the truth, the honesty, and the humanity that echoes within each one of us.

Be First to Comment