Dan Gilman was raised in a very distinct cultural atmosphere that he can only characterize as “very religious, evangelical, and Christian nationalist.” This fundamentalist upbringing, he contends, accustomed him to a worldview that eulogized the principles of American exceptionalism, denounced the evils of communism, and drew imprecise lines regarding the separation of church and state. Gilman attributes the religious conditioning that defined the first third of his life as to why he complied when he was drafted by the United States Armed Forces in 1967.

Echoes of the Second Red Scare and McCarthyism still lingered within the cultural zeitgeist of American society in the 1960s, and Gilman reckoned that halting the spread of communism was integral to the preservation of American Christian values. “It was part of the DNA of that upbringing that was instilled in me. I took it as my responsibility and my duty as a citizen and a Christian,” he recalls. “In the religious bubble you know that God will take care of you. That motivated me to be the best soldier I could be.” Gilman remembers a commonly sung 19th-century hymn, “Onward, Christian Soldiers,” which he says neatly encapsulated his community’s cultural association with religious devotion.

Typically, when one enlists in the military, the common procedure is to take the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB) Test, which is a multi-aptitude test designed to determine what branch of the military the testee will operate in. Gilman was assigned to be in the medical field, a crucial decision he says that he had “lucked out.” After three months of training, he was transferred to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, to serve with an artillery battalion. Gilman says that his duties at Fort Bragg were not particularly arduous. “You give the soldiers their shots, you take care of them as they get colds, and you keep their records straight.”

While Gilman was attending to his medic duties in Fort Bragg, a war was raging thousands of miles across the Pacific Ocean.

’69 in Vietnam

The year was 1969. The inauguration of President Richard Nixon started a prolonged effort to withdraw United States (U.S.) military entanglement in Vietnam, which manifested as a concatenation of policies commonly referred to as Vietnamization. These developments were a direct consequence of the Tet Offensive of 1968, a coordinated series of attacks on more than a hundred South Vietnamese towns executed by the Viet Cong in an attempt to sow political instability. This resulted in the culmination of the Vietnam War, as well as a discernible decline of American civilian support for U.S. involvement in the conflict.

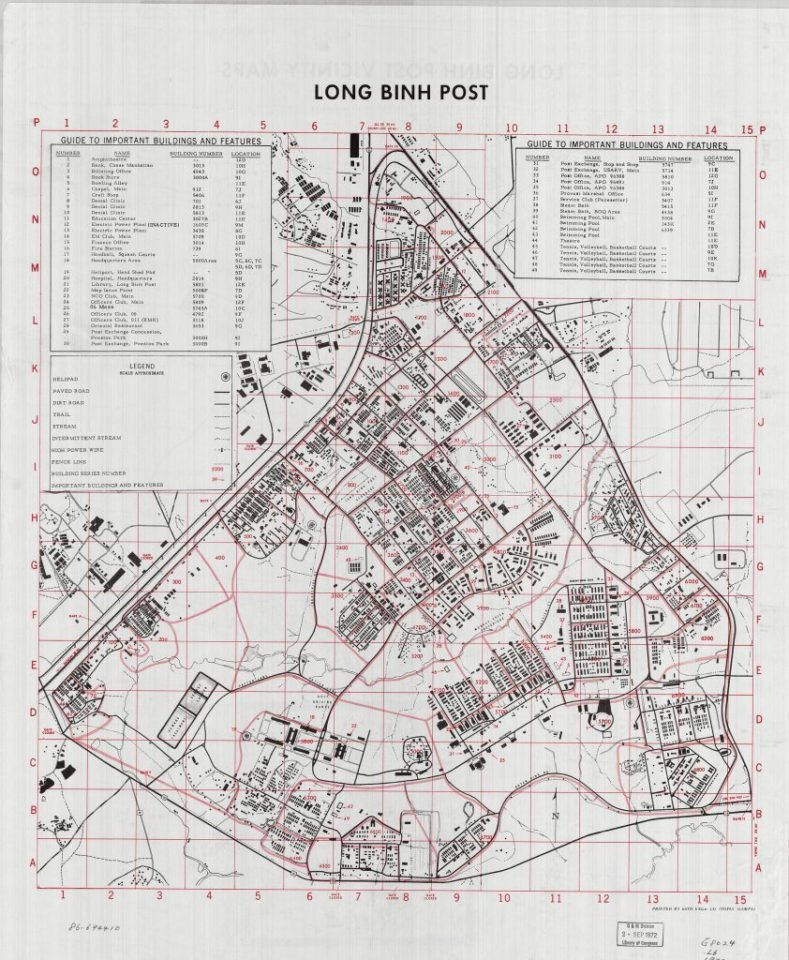

1969 transpired to be a life-changing year for Dan Gilman, who received orders to embark on a tour of Vietnam as a medic for an engineering battalion at the largest U.S. military base in the country. Constructed in 1965, at its height, Long Binh Post accommodated 60,000 personnel. The base resided between Biên Hòa and Vietnam’s capital, Ho Chi Minh City, formerly known as Saigon.

Gilman was a medic for an engineering battalion. His responsibilities mostly corresponded with his tasks at Fort Bragg, with a few stark differences. Aside from treating common colds, medics in Vietnam were attending to more acute diseases, such as malaria and tuberculosis. Severe, sometimes lethal injuries soldiers would obtain from construction accidents were frequent occurrences overseen by Gilman and his colleagues. “We had a quarry outside of the base. Mining gravel and whatnot is a fairly dangerous job, and every so often you would have soldiers who didn’t strictly follow the rules,” he says. “Accidents happen, and they would get injured or blown up.”

Long Bihn Post also harbored South Vietnamese soldiers fighting alongside Americans, accompanied by translators. Gilman reminisces on fond memories he shared with his fellow medics during his time in Vietnam, in which his colleagues would embark on trips to the nearby villages every Sunday to provide medical care to the local civilians. “The kids would just swarm to your vehicle and we would give out soap and toothbrushes to the Vietnamese.”

Veterans and Mental Health

Gilman also recalls some darker moments during his service. “I would learn later that suicides were fairly common in the military,” Gilman says. “You know, you would get bad news from home and just the stress of other soldiers that were doing jobs that were hard or risky.”

Released by the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, the 2022 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report documents that there were 6,146 veteran suicides in 2020, which amounts to an average of 16.1 deaths per day. “The suicide rate for veterans was 57.3% greater than for non-Veteran U.S. adults,” their findings displayed after adjusting for population sex and race differences. “There is something about military life and the way you are treated that just makes that a real problem,” Gilman says.

The legislative acknowledgment of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) as a legally recognized disability was a feat that veterans fought tirelessly for. In the 1980s, the Department of Veteran Affairs began to compensate veterans diagnosed with PTSD with disability benefits. “Vietnam veterans of America fought several years to get Congress to recognize that that is part of the injuries to soldiers,” says Gilman.

The Making of a Peace Activist

Like many of his fellow veterans, upon completion of his tour of Vietnam, Gilman was reluctant to relay his story to the Americans at home. “I didn’t really want to talk about it. It was the late stages of the war and the American public began to turn against the war.”

When he returned to the U.S., the anti-war movement was at its peak. Gilman reexamined his participation in the Vietnam War and the character of American interventionism after being influenced by the peace movement. “It had an effect on me,” he recalls. “It got me thinking about war, violence, and how we got into this thing. Was it just a mistake we made? Was it a worthy cause and we just bungled it? I had all these questions that I was on my own trying to figure it out.”

Gilman extensively researched the history of American foreign policy, its correspondence with international law, and the political significance of granting countries the right to sovereignty and self-determination.

Breaches of International Law

The United Nations (U.N.) will, under certain extenuating circumstances, authorize members to deploy the use of force for two reasons: in an act of self-defense or in agreement with the Security Council. The U.S. has conducted approximately 400 military interventions since 1776, with almost half of those occurring since the founding of the United Nations Security Council in 1945. Regardless of whether the government officials were freely elected, many of these foreign interventions were intended to instigate regime change. U.S. interventionism additionally is executed through the means of sanctions, as observed in the ongoing U.S.-funded humanitarian crisis in Yemen and the decades-long embargo on Cuba. “The U.S. has been to war dozens and dozens of times and never had authorization by the security council,” Gilman remarks. “You come to realize that you are in a country that isn’t abiding by and giving credence to laws and bodies that are there to have some kind of law and order to our international community.”

The U.S. historically has had a complex relationship with international law, a conceptual framework that the government vocalizes their support for, yet fails to abide by in their foreign policy decisions. In regard to Vietnam, the U.S. was never granted authorization to use force by the U.N. Security Council, which gives the Vietnam War little basis in legality in the eyes of international law. The actions of the U.S. also frequently violated international humanitarian law. These breaches were frequently observed in the targeting of civilians, as seen in the 1968 Mai Lai Massacre and the extensive napalm, white phosphorus, and cluster bomb campaigns that destroyed civilian infrastructure, as well as contributed to the North Vietnamese civilian death toll from American bombing that is estimated to be around 65,000.

French Colonialism in Vietnam

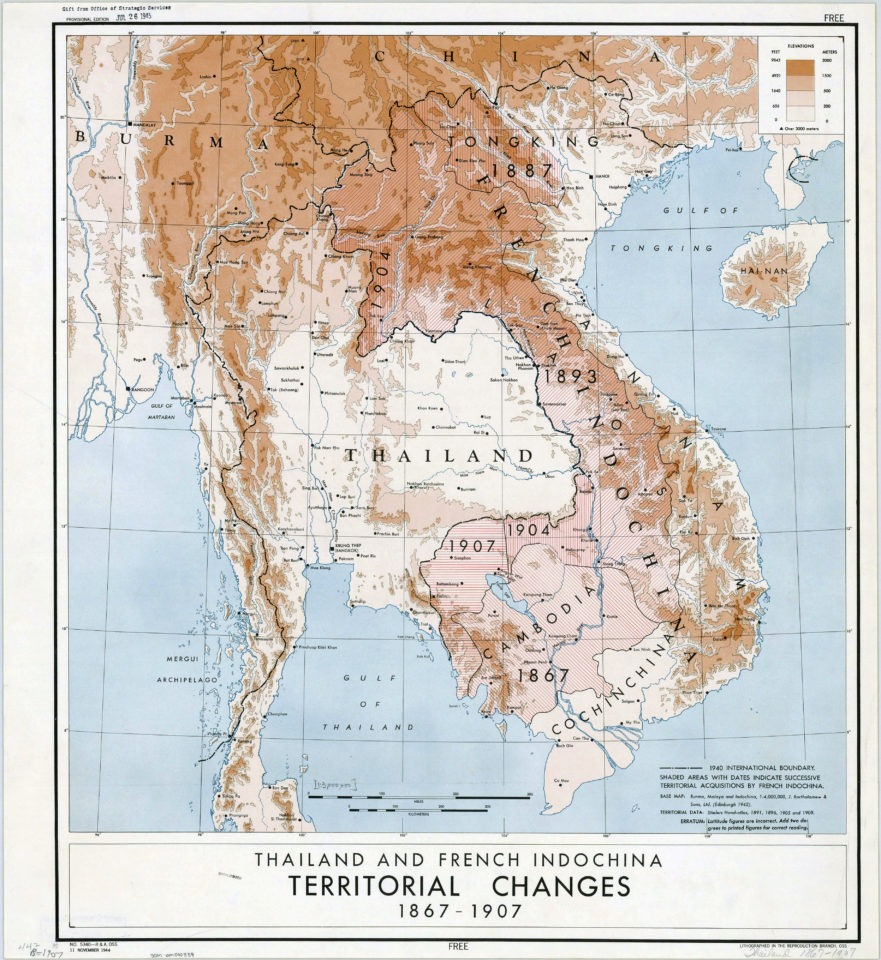

Gilman’s ideological journey began upon his research into the events leading up to the Vietnam War. For starters, he learned that foreign intervention in Vietnam and the greater Indochina region did not begin and end with the U.S.

Under the military leadership of General Paul Doumer, France seized control of Vietnam in 1887. This conquest established the beginning of French Indochina, a region in Southeast Asia composed of territories that were under the colonial governance of France until its demise in 1957. At its height, French Indochina was a bloc made up of three countries: Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam.

Anti-colonialist revolts, Japanese military occupations, and border disputes created the political and economic turmoil that would give to the rise of Ho Chi Minh, a Marxist-Leninist revolutionary that spearheaded the guerilla Vietnamese nationalist independence movement.

Regarding the conditions of Vietnam under French colonial rule, Minh remarked in the 1954 “Proclamation of Independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam“: “In the field of politics, they have deprived our people of every democratic liberty. In the field of economics, they have fleeced us to the backbone, impoverished our people, and devastated our land. They have robbed us of our rice fields, our mines, our forests, and our raw materials. They have monopolized the issuing of bank-notes and export trade. They have hampered the prospering of our national bourgeoisie; they have mercilessly exploited our workers.”

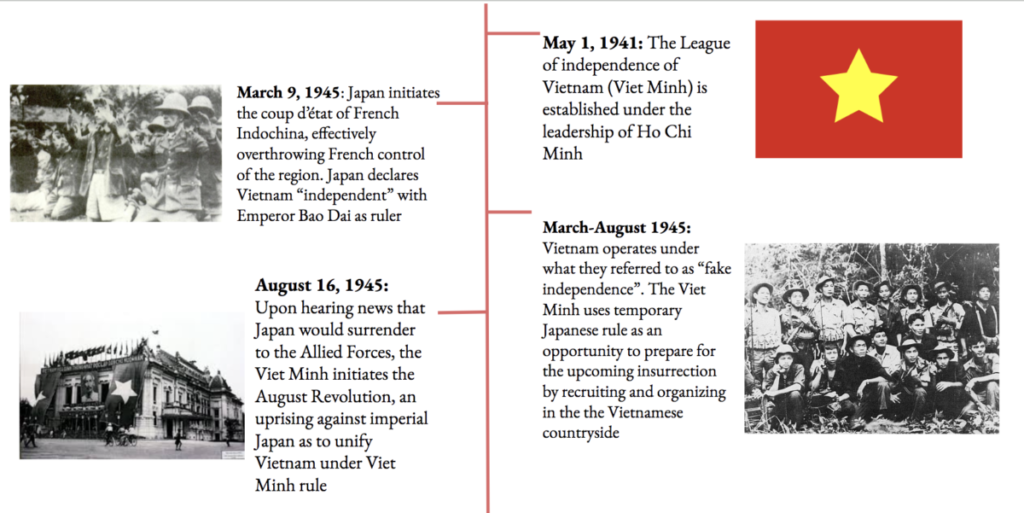

The nationalist alliance known as the Viet Minh, or the League of Independence of Vietnam, was founded and led by Ho Chi Minh and fought the First Indochina War against the French.

Why Vietnam?

Politicians such as President Lyndon B. Johnson and Henry Kissinger publicly maintained that the justification for going to war with Vietnam was born out of a non-negotiable principle to prevent the spread of communism to pro-western South Vietnam, which broke off from the communist North Vietnam in 1954. Politicians asserted that the U.S. did not begin to intervene in Vietnam until the Viet Cong, under the direction of North Vietnam, launched a military offensive in the south in 1955. However, the U.S. had been acutely involved in the Indochina region since 1950.

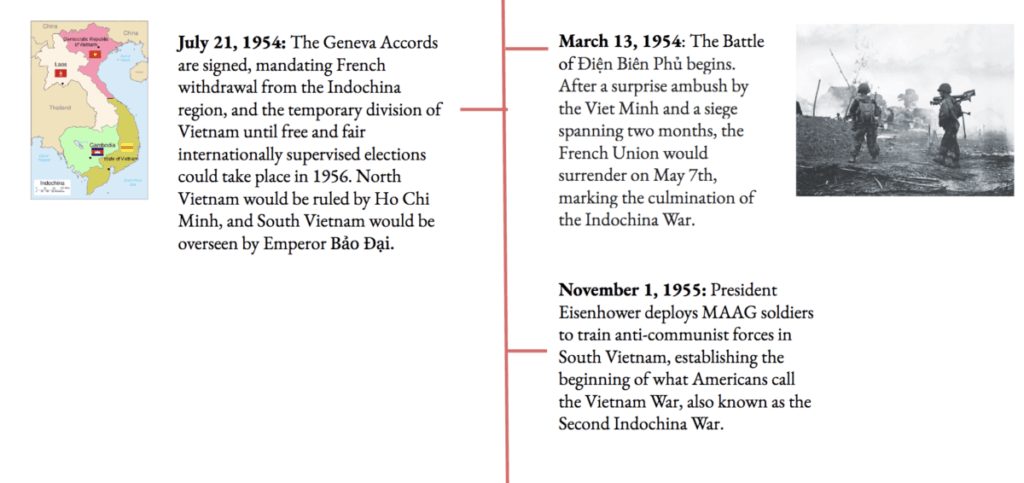

What follows is a condensed timeline of events leading up to the Vietnam War and U.S. involvement in such:

For Gilman, learning about American interventionism punctured a hole in the narratives spun by American politicians, riddled with vague jingoist platitudes about democracy and American values. “Of course, if the United States really believed they were promoting democracy and freedom, they would have abided by the Geneva Conference that ended the French effort to recolonize Vietnam,” Gilman says. “Part of the Geneva Conference was that after two years, there would be a vote for all of Vietnam to determine who would be the leader. And of course, the U.S. understood that Ho Chi Minh would win. So they knew they couldn’t retake the north.”

Seattle Veterans for Peace

Today, Gilman is a member of the Seattle chapter of Veterans for Peace, an anti-war organization composed of multigenerational veterans who wish to inform civilians of the harsh realities of war. One of the ways Gilman and his fellow activists seek to disperse these messages is through their counter-recruiting efforts. The U.S. military has a program in which they send personnel to visit American public schools. Signed into law on Jan. 8, 2002, by President George W. Bush, the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 requires schools to give military recruiters student contact information for recruitment purposes, given that the school has previously given out that information to other colleges and businesses, unless the student has specifically requested against it. The No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 is a strong contributing factor as to why military recruiting events are commonplace at American public schools, and why many American students will recognize emails and text messages from military recruiters.

Veterans for Peace attempts to combat the influence of military recruiters by attending school events alongside them, informing students of the harsh realities of the armed forces, and offering an alternative. This, Gilman says, is one of the many ways anti-war activists can attempt to avert the authority of pro-war propaganda that is fabricated into pop culture and entertainment, and even woven into the minutiae of American life. “You see it at sports events. The fly-overs, the flags, people parachute down into football fields,” Gilman reflects. “It’s really just a part of our culture. The military is ingrained into our society.”

Author

Catherine Maund is a staff writer at The Seattle Collegian with an avid interest in American foreign policy, government surveillance, private interest groups with an influence on legislation, and animal welfarism. She hopes to pursue a career in investigative journalism.

Be First to Comment