Acquiring the Taste: The obscurity and quality of Gentle Giant

There’s a common trope among musicians and music fans involving the popularity of music, or lack thereof. One person might decry another’s favorite artist as “too mainstream,” disqualifying or invalidating their output by that metric. A fan of grunge music whose favorite band is Nirvana might hear that the band has become overplayed and lost its edge due to success, and that real, hardcore grunge fans only listen to a garage band formed in Klamath Falls, Oregon in 1991 that nobody’s ever heard of.

Of course, everyone is entitled to their opinion, but some seem to directly associate obscurity and quality. But wouldn’t the best, most talented musicians rise to the occasion and garner the most fame? Why would they wilt in obscurity if their music is better than that of those basking in success? At the end of the day, it comes down to appeal. The objective quality of the music becomes irrelevant in this measure; it’s all about how many people want to listen to it and whether they want to listen to it more than once.

Rating it based on both objective compositional sophistication and potential for appeal, this review will assess an example of a phenomenal musical construction that is considered relatively obscure, even within its own genre: Gentle Giant’s 1972 album Acquiring The Taste.

Most listeners of rock music are familiar with the subgenre of progressive rock, also known as prog: it’s set apart from most rock music by its complexity, employing unusual time signatures (think 7/4 and 5/4) and chords that stray from the pop mold. Some of the more recognizable prog rock bands are Pink Floyd, Kansas, Rush, and Yes.

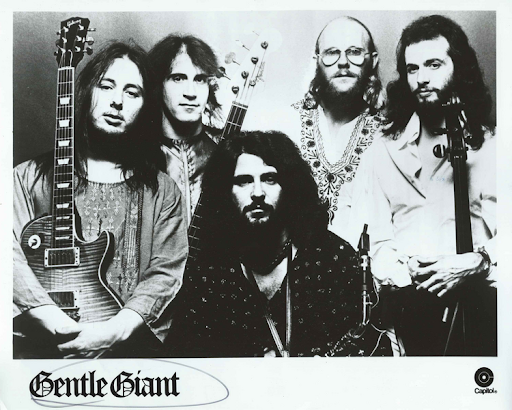

Few other than the most devoted prog fans, however, would recognize the name Gentle Giant. A British band that was active throughout the 1970s, their music is intricate but often intimidatingly so. Acquiring The Taste is the group’s second studio album.

Befitting the theme of this review, a note on the sleeve of the album reads, “It is our goal to expand the frontiers of contemporary popular music at the risk of being very unpopular. We have recorded each composition with the one thought–that it should be unique, adventurous and fascinating. It has taken every shred of our combined musical and technical knowledge to achieve this. From the outset we have abandoned all preconceived thoughts of blatant commercialism. Instead we hope to give you something far more substantial and fulfilling. All you need to do is sit back, and acquire the taste.”

Side One

Acquiring the Taste opens with the song “Pantagruel’s Nativity.” The title alone gives us an idea of the depth of the record: it references “The Life of Gargantua and Pantagruel,” a collection of satirical French Renaissance novels dating back to the 16th century. The first noise of the album is a plaintive synthesizer theme, sounding like the accompaniment to a Star Trek episode. This quickly fades into a slow, melodic folk tune, with violins, flutes, and trumpets backing a soft singing voice. These peaceful verses are occasionally broken by an abrasive guitar riff and drums. As the song enters its B-section, the guitar takes the front role, repeating another angry riff. An almost operatic, wailing chorus backs up the guitar. Out of nowhere comes a jazzy vibraphone solo, followed by a hard rock guitar solo, before the gritty B-section concludes and we return to the folky A-section.

“Edge of Twilight” comes next, a trippy, jazzy piece that could be likened to a Christmas carol on bath salts. The song displays a few interesting motifs, and a timpani solo which you’d be hard pressed to find in rock music other than Jethro Tull. The following song however, “The House, The Street, The Room,” is nothing short of spectacular. Carried by a jolting, unpredictable riff and enthusiastic vocals, this entire song is a ride. The melody bucks like a bronco, from fiery hard rock to delicate folk, then back to rock before you even notice. There is no regard for sticking to a key as the band fluently alternates between major and minor tonations. If The Beatles had been exponentially better musicians, I’d wager it would sound a lot like this. One vicious, no-holds-barred guitar solo backed by agonizing keyboards later and we’re back to the chorus as the song finishes with gusto. Side one finishes with the title song, a short, synthesizer-dominated instrumental that wraps up the first half of the album nicely.

Side Two

Side two kicks off with a bang. “Wreck” is another piece led by a powerful guitar riff; by nature of this hard rock tincture, it already has more mainstream appeal than the entirety of the album’s first side. If I was listening without context, I could easily confuse the band for Kansas. This piece, unlike the majority of the album, stays in 4/4 (for those less familiar with musical terms, the most common, straight-forward time signature.) Perhaps this was Gentle Giant attempting a stab at radio airplay… although just as I’m writing this, the song features a pan flute solo, so perhaps not.

“The Moon is Down” comes next. It opens almost amedelodically, a sharp contrast from the previous song, meandering through the major and minor scales haphazardly as the lead singer croons. The time signature is also much more complex and even hard to follow at times, which is to be expected by this point. While this whimsical song might not stand out to an unaccustomed audience, it confirms the sheer technicality of this band; many far more acclaimed rockers of the era would find themselves flabbergasted trying to keep up with just the chord changes.

The penultimate song on the album, “Black Cat,” showcases a deft theme played on violins and cellos with a drumset holding it down behind them, a unique but effective combo that helps the gentle vocals of the song stand out. A B-section follows that might sound chaotic and random to the untrained ear, but is in fact incredibly ornate.

Finally, we’ve reached the last song on the album: “Plain Truth” is power folk rock, with occasional sprinkles of prog mixed in to distinguish it. Gentle Giant had a knack for catchy guitar riffs that take unexpected turns, making them even more memorable. The majority of the song is instrumental shredding, mimicking the best of American folk rock, with a British hard rock angle and Gentle Giant’s always-present weirdness preventing the song from being generic. Every now and then, the band launches into the chorus, with powerful bass guitar on each off-beat, emphasizing the vocals: “Don’t look for something, plain truth is nothing, nothing but the plain truth.”

Conclusion

★★★★☆

As much as the prog fan in me would love to give this album 5 stars, I’m forced to consider all the factors in an objective review, including general appeal. While Gentle Giant’s technical ability and musicality are off the charts and incredibly impressive, the interest from a more mainstream audience might be lacking, as some of the songs have long-winded instrumental sections, as well as oddball orchestration and bizarre arrangements that are liable to scare off casual listeners. This explains their lack of commercial success with Acquiring the Taste and in general, but as the album’s sleeve note details, this didn’t bother the boys in the band. To quote former Kansas frontman Kerry Livgren, “I think they fulfilled their prophecy of their own obscurity.”

However, between the searing guitar riffs, specifically on “Wreck” and “Plain Truth”, and constantly shifting musical patterns, vibrant motifs, and time signatures, this last thing you could describe this album as is boring. Almost every song has the ability to keep the listener engaged, albeit possibly confused. For those with an interest in rock music, especially those intrigued by prog, Gentle Giant’s discography could keep you occupied for a long while.

Kayvon Bumpus was The Seattle Collegian's Managing Editor. An immersed writer, lifelong musician, and Seattleite, he hopes to use journalism to elucidate and convey varieties of knowledge - a worthwhile endeavor in our current age of distraction and disinformation.