Improving gut health can be a significant change for physical, mental health

Our gut is an intricate web of various kinds of microorganisms — bacteria, fungi, and other living creatures that are collectively known as gut flora. It sounds a bit intimidating to think of the trillions of living microorganisms inside of you, but these little friends within our bodies play crucial roles in our physical and mental health.

Beneficial gut microbes order specialized immune cells to produce antiviral proteins that ultimately eliminate external infections, thus supporting our immune systems. Many studies have shown that individuals with an unhealthy function of gut bacteria have a higher chance of developing depression and anxiety. After all, it is no accident that our gut is referred to as our “second brain.”

As a student who struggles with a lot of digestive issues, I can testify that focusing on my gut health has not only helped me to maintain my status as a college student (I would not have been able to continue my classes without knowing how to take care of my gut health), but I believe it has immensely benefited my mental stability. Therefore, when it came to improving my physical as well as mental well-being, a great way for me to start was by paying attention to my gut health.

First, let us talk about the gut microbiome. Imagine you are seeing a forest from above. Forests are clustered with flowering trees and evergreen shrubs, a seemingly thriving wilderness that inhabits many different kinds of species and life forms, each having its own role in maintaining ecological balance.

At a microscopic level, our gut microbiome is the same. Diverse kinds of bacteria coexist peacefully and are scattered throughout our body, with the largest number found in our small and large intestines. The presence of balanced bacteria in our bodies is significant to maintaining good health.

Over the years, many studies have shown that an imbalanced gut microbiome leads to a number of gastrointestinal conditions, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). It also can contribute to a wider manifestation of diseases like obesity, type 2 diabetes, and atopy.

In a study conducted by Stanford scientists, researchers found a link between ulcerative colitis (IBD) and depleted gut microbes. When the researchers compared two groups of patients — one group composed of patients with ulcerative colitis, and a group of people with a noninflammatory gut disease — who had undergone the same corrective surgery, they found that the patients with IBD were missing important gut microbes that keep the inflammation at bay.

“All healthy people have Ruminococcaceae in their gut, but in the UC pouch patients, members of this family were significantly depleted,” said Habtezion, one of the leading research scientists of the patients with IBD.

Not only is there an association between depleted gut bacteria and a number of physical diseases, there is also a growing amount of evidence showing that poor gut health is directly correlated with an array of mental health issues.

For decades, scientists around the globe thought depression and anxiety led to gastrointestinal problems, but recent findings conducted by Johns Hopkins University’s researchers tell a different story. It is not depression that leads to less diversity of friendly bacteria in our bodies, but the lack of good bacteria that contributes to depression.

By having less variety of friendly bacteria in the digestive system, a person can develop irritations in their gastrointestinal systems, which “sends chemical signals to the central nervous system and trigger mood changes,” according to the university’s medicine department. Therefore, it is increasingly crucial to put more effort into maintaining a balanced gut microbiome to have reduced stress and improved mental stability.

Setting the complicated research studies aside, let’s talk about the steps involved in nurturing balanced gut flora. These mainly include dietary management, such as adding fermented foods, raw milk, and kefir, as well as completing daily exercises and stress management techniques.

Let’s first discuss the role fermented foods play in our gut health and how exactly they boost good bacteria in our bodies. Fermented foods, such as sauerkraut, kimchi, and other fermented pickles, are rich in microorganisms called lactobacillus. For a long time, lactic acid bacterias have been known as effective probiotic microorganisms for disease treatments and health restorations. In fact, a research study conducted by scientists from Stanford University found that individuals were able to reduce their inflammation after following a 10-week fermented foods rich diet.

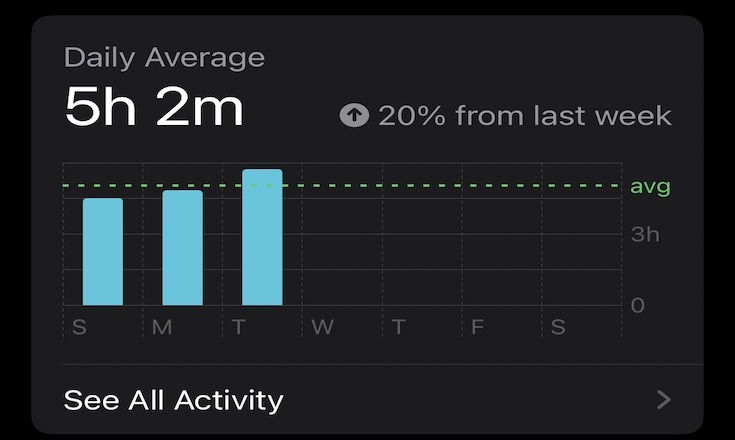

Doing daily exercises has also been shown to contribute to increasing the diversity of gut bacterias. Alteration in the gut microbiome can be achieved by following simple exercises like walking. One study found that women who performed at least three hours of brisk walking per week have increased levels of good bacteria such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia hominis, and Akkermansia muciniphila. These bacteria are known for decreasing inflammation and have been associated with a lower body mass index (BMI). Doing light, yet consistent exercise every day can definitely influence the diversity of the gut flora.

Finally, stress management techniques such as mediation practices, breathing exercises, and yoga have positive effects on both relieving gut-related symptoms and aiding digestion. For example, one study found that, compared with the subjects in the healthy control group who never received any meditation training as part of their daily activities, the people who followed a long-term vegan meditation practice had more diversity in their gut flora.

In “The Mind-Gut Connection,” Emeran Mayer, M.D., explores the constant dialogue between our gut, brain, and the gut microbiome. Nerve signals in the brain transmit chemicals to the gut, which change the composition of the gut microbiome and influence its behavior, leading to conditions like leaky gut — a digestive condition that affects the lining of the intestine.

From an evolutionary point of view, short-term stresses, such as fight or flight responses, no doubt allowed our predecessors to avoid predators in their environment and ultimately save their lives. But a prolonged state of being in constant stress is more harmful rather than helpful to our health.

Among the vast research on the gut microbiome, there are numerous studies that are trying to understand the relationship of gut health to both our mental and physical health. For many college students, depression and stress are highly discussed topics as they are the most recurring mental health problems in college life. Yet, because of the many time constraints put forward by academics and social activities, rarely do students have enough time to eat healthily, exercise daily, and practice stress management techniques.

Combined with the stress coming from these daily busy schedules, students have a higher chance of decreased friendly gut bacteria. However, by implementing the habits that are directed toward improving their gut health, students can lead a more fulfilled and successful college life.

Chin-Erdene is an international student at Seattle Central College and a member of the Editorial Board of Seattle Collegian. He is currently pursuing a degree in computer science and linguistics and aspiring to become a linguistics engineer in the future. As he is from Mongolia, he only started to learn English in the latter part of his high school years, from which he developed a deep passion for linguistics and language structures. He wants to use the applications of computer science and mathematics to analyze written and spoken languages from computational perspectives. In his free time, he loves reading science fiction books, baking sourdough bread, and watching action/sci-fi movies. He is a big fan of Goerge R.R Martin and J.R.R Tolkein.