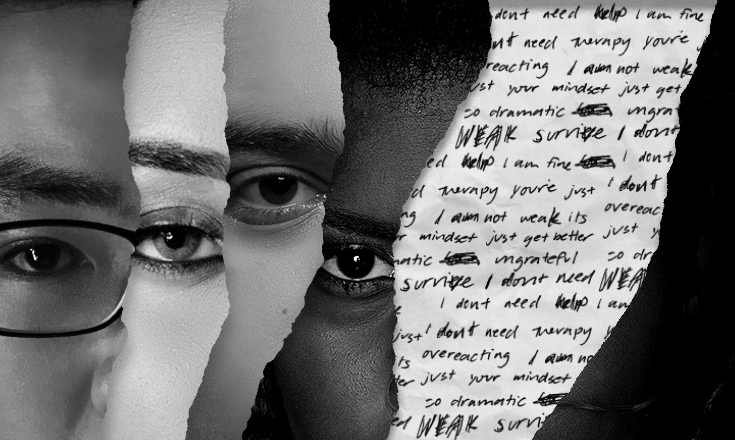

According to a research article in BMC Public Health, the stigma of mental illness is higher among ethnic minorities than among majorities. Stigma is an intricate problem that involves self, public, and structural components. It affects people dealing with mental illnesses, their support systems, and healthcare services. Knowledge of mental illness and cultural relevance mitigate the effects of stigma. Comprehending stigma is pivotal to reducing its adverse impacts on people of color (POC) seeking treatment. Moreover, sustainable solutions cannot be implemented without a deeper understanding of stigmas.

The mental health stigma in Black communities can be traced back to the dark days of slavery. To fully grasp how deep the stigma runs in Black communities, you have to look at it from a cultural and historical perspective. From the outset of the 1600s, science was used as a justification to classify mental health into black-and-white diseases. The likes of Benjamin Rush and Samuel Cartwright came up with diseases like negritude and drapetomania that had no factual basis. For instance, Cartwright invented dysaesthesia aethiopica, a disease “affecting” only enslaved Black people, which was marked by extreme laziness, insensitivity to pain, and a tendency to destroy things. On the other hand, enslaved people were thought of as inferior and incapable of harboring depression, anxiety, and other mental illnesses in order to undermine their humanity. The mentality induced by theories like these initiated a perception that Black people have biological defects tied to their race.

It is crucial to be cognizant that the stigma in Black communities is intimately tied to systemic racism, colonialism, and slavery. Black people fear getting diagnosed with mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder because these mental illnesses are criminalized. A great number of research articles asserted that the disorders were manifested by rage, volatility, and aggression, and that it was a condition that afflicted “Negro men.” This paved the way for the justification of Jim Crow laws, police brutality, and mass incarcerations in prisons and psychiatric hospitals. The misguided view that vilified African American activism as a mental illness created a barricade for people with actual mental illnesses. Instead of finding sustainable solutions, some state hospitals presided over by white administrators employed unlicensed doctors to administer massive amounts of electroshock and chemical “therapies” and required Black patients to work in the fields as if the hospitals were plantations. Some mental illnesses, like schizophrenia, are overdiagnosed while others, like depression, are underdiagnosed, with symptoms mistaken for criminal behavior that requires punishment. Prisons indefinitely replaced hospitals, and sadly that is still the case today.

An impediment when seeking treatment for mental illnesses in Black communities is the impression that it is a sign of weakness. Looking back at history, the survival of Black people was nothing short of a miracle. African Americans endured with grit being dehumanized and degraded to nothing more than mere property; Surely that chips away at a person’s mental well-being. The survivalist mentality that has been ever present since shapes the narrative along the lines of: We have overcome unimaginable adversity yesterday and today, and no mental illness is going to overtake us. In some Black cultures, depression and anxiety are viewed as weaknesses, and to conquer them, you need to have willpower.

Mental health is stigmatized in Asian communities as well, mainly because of cultural beliefs. The concept of saving face plays a major role in the stigmatization of mental health because it threatens the social standing of a family in the community. Men are affected most in this case because of the need to show masculinity and not weakness. Having a mental illness is also perceived as having no identity, being defective, and being valueless to the community. Furthermore, the “model minority” myth enforces the idea that Asian Americans are hardworking, intelligent, and educated. This puts pressure on Asian Americans to meet these high expectations without complaining, having setbacks, or failing. A lack of mental health awareness reinforces negative stereotypes and causes people to discount, deny, or ignore mental health symptoms.

The stigma of mental health is not exclusive to only one particular POC community. I interviewed Maeve Le, a student at Seattle Central College from Vietnam. Le explained in detail the overwhelming stance of her community in regards to mental health.

Fatimah Abdullahi: Is there a stigma of mental health in your community?

Meave Le: I would say yes, there are many people not only from Vietnam, but also from other Asian countries who refuse to acknowledge that their kids have mental illnesses. Our parents and the older generation perceive things differently. I’ve never heard anyone using the term “therapist” in Vietnam. It’s not that we don’t have any, we just don’t need them. Our parents expect us not to have a therapist; they think we can always solve our problems on our own.

FA: Why do you think there is a stigma of mental health in your Vietnamese community?

ML: From the lack of understanding about different types of mental illnesses, and from people who already have negative attitudes toward that kind of topic.

FA: Are the people in your community starting to open up about mental health?

ML: No and yes. I can’t change the way my parents think about that. But as someone who’s from a younger generation, I understand that people should deserve help and they can always talk about their problems to someone they trust most, preferably a therapist.

FA: Do you think people approach mental health the same as they did a couple of years ago?

ML: Fortunately, they do not. This generation has started approaching mental health in a positive way. They understand that mental health stigmas are daunting enough, and they also create a blockade for people dealing with mental health to seek medical intervention early on. The approach to that topic also depends on who you are with and how they think about it because people perceive things through different lenses.

Hangatu Daud, a clinical therapist, asserted that marginalized communities distrust the healthcare system because the United States has a long history of malpractices and using minority communities such as Indigenous Native Americans, African Americans, and Asian Americans to experiment with new drugs without their consent; the Tuskegee syphilis experiment is an example. This makes it harder for individuals suffering from mental health to seek out treatment due to mistrust or fear of being mistreated. Moreover, Daud noted that more than half of white therapists and providers are not culturally proficient when dealing with POC.. Cultural biases and insensitivity to cultural differences affect minority groups’ quality of care.

Professor Shaan Shahabuddin, a psychology instructor at Seattle Central College, professed, “An overlooked stigma of mental health in POC communities is the association of mental health services with privilege. There is less access to mental healthcare among racial and ethnic minorities and low-income individuals than among wealthier white Americans.” According to Shahabuddin, due to marginalization, most POC communities don’t have the luxury of worrying about mental health because they are already dealing with poverty, lack of housing and food, and the disparities that exist in the healthcare system. Furthermore, a colossal number of people still can’t afford mental health services even if they wanted to. Accessibility to high-quality mental health services is a right everyone should equally have in Shahabuddin’s eyes.

Mental health is not an easy thing to deal with in marginalized communities. Racism, colonialism, and whole systems are stacked against POC in this country. Discerning where these stigmas come from is imperative in moving forward. In spite of the extensive adverse history of mental health, we can change our attitude toward mental health and overcome the barriers that prevent many POC from receiving the treatment they need. Supplementary to shifting the negative narrative encompassing mental health, there are other barriers like access to health and cost of care that need to be addressed. It is possible to destigmatize mental health by discussing it more openly and by being educated about different types of mental illnesses and their symptoms.

Author

Fatimah Abdullahi is an International student at Seattle Central College.

She is from Kenya, Nairobi, but ethnically Somali. She is currently pursuing her Associate of Science in Computer Science. She wishes to transfer to a 4-year university to get her Bachelor's and Master's in Computer Science. Although she is in the field of STEM, she has a passion for writing. Fatima is a staff writer at The Seattle Collegian whose love for writing stems from reading different genres. Her purpose on writing is to create stories that evoke emotion and incites change in herself and her audience.

Be First to Comment